In the aftermath of World War I, the Polish–Soviet War (14 February 1919 – 18 March 1921) was fought principally between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic on areas previously controlled by the Russian Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Following the collapse of the Central Powers and the 11 November 1918 Armistice, Vladimir Lenin's Russia annulled the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (which it had signed with the Central Powers in March 1918) and began slowly moving forces westward to reclaim and secure the lands vacated by German forces that the Russian state had lost under the treaty. The newly independent Poland (created in October–November 1918) was seen by Lenin as the bridge that his Red Army would have to cross in order to assist other communist movements and bring about other European revolutions. At the same time, leading Poles of various political stripes pursued the common goal of restoring the country's pre-1772 borders. Polish Chief of State Józef Pisudski (in office since November 14, 1918) was inspired by this notion and began deploying soldiers east.

While the Soviet Red Army was still involved with the 1917–1922 Russian Civil War, the Polish Army seized the majority of Lithuania and Belarus in 1919. Polish forces had acquired control of much of Western Ukraine by July 1919, and the Polish–Ukrainian War, which lasted from November 1918 to July 1919, had ended in victory. Meanwhile, on Ukraine's eastern borderlands with Russia, Symon Petliura attempted to protect the Ukrainian People's Republic, but as the Bolsheviks took control of the Russian Civil War, they marched westward into the disputed Ukrainian borders, forcing Petliura's soldiers to retire. Petliura was forced to seek an alliance with Pisudski after being reduced to a small area of land in the west. The alliance was officially completed in April 1920.

Pisudski believed that armed action was the best option for Poland to secure favorable borders, and that he could easily beat Red Army forces. His Kiev Offensive, which is often regarded as the start of the Polish–Soviet War in its strictest sense, began in late April 1920 and ended on May 7 with the seizure of Kiev by Polish and allied Ukrainian forces. The area's lesser Soviet armies had not been beaten because they avoided big clashes and withdrew.

The Red Army successfully counterattacked the Polish offensive beginning on June 5 on the southern Ukrainian front and on July 4 on the northern front. While the Directorate of Ukraine withdrew to Western Europe, the Soviet offensive pushed Polish forces westward all the way to Warsaw, Poland's capital. Fears of Soviet soldiers approaching German borders piqued Western powers' interest and engagement in the conflict. The surrender of Warsaw seemed inevitable in mid-summer, but the tide had shifted again in mid-August after the Polish forces won an unexpected and decisive victory at the Battle of Warsaw (12 to 25 August 1920). Following the eastward Polish advance, the Soviets requested peace, and the conflict ended on October 18, 1920, with a ceasefire.

On March 18, 1921, the Treaty of Riga was signed, dividing the contested regions between Poland and Soviet Russia. For the rest of the interwar period, the Soviet–Polish border was set by the war and treaty discussions. The Curzon Line (a 1920 British proposal for Poland's border, based on the version accepted in 1919 by the Entente leaders as the eastern limit of Poland's growth) was formed about 200 kilometers east of Poland's eastern border. Ukraine and Belarus were divided between Poland and Soviet Russia, both of which founded Soviet republics in their respective regions of the country.

The peace talks, which were mostly led by Pisudski's opponents and against his desire on the Polish side, ended with the official recognition of the two Soviet republics, who became treaty parties. This result, as well as the new border agreed upon, ruled out the construction of the Intermarium Polish-led federation of states, as well as the achievement of Pisudski's other eastern-policy objectives. The Soviet Union, which was founded in December 1922, later used the Ukrainian Soviet Republic and the Byelorussian Soviet Republic to claim unification with parts of the Kresy territories where East Slavics outnumbered ethnic Poles and had remained on the Polish side of the border, without any form of autonomy, after the Riga Peace.

The war is known by several names. "Polish–Soviet War" is the most common but other names include "Russo–Polish War" (or "Polish–Russian War") and "Polish–Bolshevik War". This last term (or just "Bolshevik War" (Polish: Wojna bolszewicka)) is most common in Polish sources. In some Polish sources it is also referred as the "War of 1920" (Polish: Wojna 1920 roku).

There is disagreement over the dates of the war. The Encyclopædia Britannica begins its "Russo-Polish War" article with the date range 1919–1920 but then states, "Although there had been hostilities between the two countries during 1919, the conflict began when the Polish head of state Józef Piłsudski formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlyura (21 April 1920) and their combined forces began to overrun Ukraine, occupying Kiev on 7 May." Some Western historians, including Norman Davies, consider mid-February 1919 the beginning of the war. However, military confrontations between forces that can be considered officially Polish and the Red Army took place already in late autumn 1918 and in January 1919. The city of Vilnius, for example, was taken by the Soviets on 5 January 1919.

The ending date is given as either 1920 or 1921; this confusion stems from the fact that while the ceasefire was put into force on 18 October 1920, the official treaty ending the war was signed on 18 March 1921. While the events of late 1918 and 1919 can be described as a border conflict and only in spring 1920 did both sides engage in an all-out war, the warfare that took place in late April 1920 was an escalation of the fighting that began a year and a half earlier.

The primary battlegrounds of the conflict are what is now Ukraine and Belarus. They were a part of the medieval realm of Kievan Rus' until the mid-13th century. The areas were objectives of expansion for the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania after a period of internal conflicts and the 1240 Mongol invasion. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania annexed the Principality of Kiev and the territory between the Dnieper, Pripyat, and Daugava (Western Dvina) rivers in the first half of the 14th century. The Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia was split between Poland and Lithuania in 1352. According to the provisions of the Union of Lublin between Poland and Lithuania, some Ukrainian territory were transferred to the Polish Crown in 1569. During the Partitions of Poland–Lithuania, several East Slavic areas became part of the Russian Empire between 1772 and 1795. Poland lost its legal independence in 1795 (the Third Partition of Poland). Much of the territory of the Duchy of Warsaw was transferred to Russian rule after the Congress of Vienna in 1814–1815, and established the autonomous Congress Poland (officially the Kingdom of Poland). Tsar Alexander II robbed Congress Poland of its unique constitution, attempted to force general use of the Russian language, and seized enormous tracts of territory away from Poles when young Poles opposed conscription to the Imperial Russian Army during the January Uprising of 1863. Congress Poland was divided into ten provinces, each with a Russian military governor and all under the complete administration of the Russian Governor-General at Warsaw.

The map of Central and Eastern Europe changed dramatically in the aftermath of World War I. The collapse of the German Empire rendered Berlin's plans for the construction of German-dominated states in Eastern Europe (Mitteleuropa), which included a new version of the Kingdom of Poland, obsolete. The Russian Empire fell apart, resulting in the Russian Revolution and the Civil War in Russia. The German invasion and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed by the newly formed Soviet Russia, cost the Russian state territory. Several nations in the region recognized an opportunity for independence and took advantage of it. Following Germany's defeat in the west and the departure of German forces in the east, Soviet Russia disavowed the treaty and went on to reclaim many of the Russian Empire's former lands. However, because of the civil war, it lacked the resources to respond quickly to nationwide uprisings.

Poland became a sovereign state in November 1918. The successful Greater Poland rebellion (1918–1919) against Germany was one of the several border conflicts conducted by the Second Polish Republic. In the east, the historic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth comprised extensive lands. They were included into the Russian Empire between 1772 and 1795, and remained as the Northwest Territory until World War I. Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Lithuanian, and Latvian interests fought over them after the war.

Józef Pisudski had a big influence on politics in newly independent Poland. The Regency Council of the Kingdom of Poland, a council installed by the Central Powers, appointed Pisudski as the leader of the Polish armed forces on November 11, 1918. Many Polish officials accepted him as a temporary chief of state, and he exercised vast powers in practice. He was appointed Chief of State under the Small Constitution of February 20, 1919. As a result, he was required to report to the Legislative Sejm.

Almost all of Poland's neighbors began battling over borders and other issues after the Russian and German occupying regimes collapsed. The Baltic Sea region has seen the Finnish Civil War, Estonian War of Independence, Latvian War of Independence, and Lithuanian Wars of Independence. Russia was engulfed in domestic strife. The Communist International was founded in Moscow in early March 1919. In March, the Hungarian Soviet Republic was established, and in April, the Bavarian Soviet Republic was established. "The fight of giants has ended, the wars of the pygmies have begun," Winston Churchill sarcastically observed in a conversation with Prime Minister David Lloyd George. The war between Poland and the Soviet Union was the longest of the international conflicts.

During World War I, the territory that would become Poland was a key battleground, and the new country lacked governmental stability. By July 1919, it had won the bloody Polish–Ukrainian War against the West Ukrainian People's Republic, but it had already been drawn into new battles with Germany (the 1919–1921 Silesian Uprisings) and Czechoslovakia (the January 1919 border conflict). Meanwhile, Soviet Russia concentrated on preventing the counterrevolution and the Allied powers' intervention in 1918–1925. The initial clashes between Polish and Soviet forces occurred in the autumn and winter of 1918/1919, but a full-scale war took a year and a half to emerge.

Any considerable territorial expansion of Poland at the expense of Russia or Germany, according to the Western powers, would be severely disruptive to the post-World War I order. The Western Allies did not want to give unhappy Germany and Russia a motive to conspire together, among other things. The advent of the unrecognized Bolshevik regime threw this logic into disarray.

Poland's western border was governed by the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed on June 28, 1919. The Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920) did not make a definite decision on Poland's eastern border, but the Allied Supreme War Council declared a provisional line on December 8, 1919. (its later version would be known as the Curzon Line). It was an attempt to identify locations with a "undeniably Polish ethnic majority." The permanent boundary was subject on future negotiations between the Western powers and White Russia, which was expected to win the Russian Civil War. Pisudski and his supporters held Prime Minister Ignacy Paderewski responsible for the outcome, leading to his removal. Paderewski departed from politics, enraged.

Vladimir Lenin, the leader of Russia's new Bolshevik government, aimed to reclaim the territories lost to Russia in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 (the treaty was annulled by Russia on November 13, 1918) and establish Soviet governments in the emerging countries in the former Russian Empire's western regions. The more ambitious ambition was to travel to Germany, where he anticipated a socialist revolution. He believed that without the assistance of a socialist Germany, Soviet Russia would perish. The Soviets had taken control of most of eastern and central Ukraine (previously part of the Russian Empire) by the end of summer 1919, and had forced the Directorate of Ukraine out of Kiev. They established the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia in February 1919. (Litbel). Because of the terror it had imposed and the collection of food and supplies for the troops, the administration there was extremely unpopular. The Soviet authorities officially denied any attempt to conquer Europe.

As the Polish–Soviet Conflict continued, especially after Poland's Kiev Offensive was repulsed in June 1920, Soviet strategists, including Lenin, began to see the war as a means of spreading the revolution westward. According to historian Richard Pipes, the Soviets had previously planned an offensive on Galicia (the disputed eastern half of which Poland had acquired during the Polish–Ukrainian War of 1918–1919) before the Kiev Offensive.

Lenin began to foresee the future of world revolution with greater hope after the Red Army's civil war successes over White Russian anti-communist forces and their Western supporters in late 1919. The Bolsheviks emphasized the need for proletarian dictatorship and campaigned for a global communist commonwealth. They planned to link the Russian revolution with a communist revolution in Germany, as well as support other communist groups in Europe. The Red Army would have to cross Poland's territory in order to provide direct physical support to revolutionaries in the West.

The situation, according to historian Andrzej Chwalba, was different in late 1919 and winter–spring 1920. Faced with waning revolutionary fervor in Europe and their own issues, the Soviets attempted to make peace with Russia's neighbors, especially Poland.

(Pisudski) "hoped to merge most of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth regions into the future Polish state by constructing it as the Polish-led, multinational federation," according to Aviel Roshwald.

[39] Pisudski planned to dismantle the Russian Empire and establish the Intermarium federation of nominally autonomous states, including Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and other Central and East European republics that had emerged from the ruins of empires during World War I. Poland, in Pisudski's view, would replace a truncated and greatly weakened Russia as Eastern Europe's great power. Negotiations would not be allowed before a military triumph, according to his strategy. He had anticipated that the new Poland-led union would act as a counterweight to Russia's or Germany's possible imperialist objectives. Pisudski believed that an independent Poland could not exist without a Ukraine free of Russian domination, hence his major goal was to separate Ukraine from Russia. He employed military force to expand Poland's frontiers in Galicia and Volhynia, as well as to destroy a Ukrainian attempt at self-determination in the disputed territory east of the Curzon Line, which had a strong Polish population. On the question of Poland's future borders, Pisudski gave a speech on February 7, 1919: "Poland currently has no borders, and whatever we can acquire in this regard in the west is contingent on the Entente – on the amount to which it wishes to pressure Germany. It's a different story in the east; there are doors that open and close depending on who forces them open and how far they open ".. As a result, Polish military troops set out to extend far to the east. As Pisudski predicted, "Closed within the 16th-century borders, cut off from the Black Sea and Baltic Sea, and robbed of the South and South-land east's and mineral richness, Russia may easily slip into the status of a second-class state. As the largest and most powerful of the new powers, Poland could easily develop a sphere of influence spanning Finland to the Caucasus "..

In comparison to the opposing National Democracy's idea of immediate annexation and Polonization of the contested eastern provinces, Pisudski's views appeared progressive and democratic, but he employed his "federation" idea instrumentally. (For the time being), as he wrote to his close collaborator Leon Wasilewski in April 1919, "I don't want to be an imperialist or a federalist. Given that, in this God's world, false language of people and nation brotherhood, as well as American petty ideologies, appear to be winning, I joyfully join with the federalists ".. The contrasts between Pisudski's vision of Poland and that of his competitor National Democratic leader Roman Dmowski, according to Chwalba, were more rhetorical than substantive. Pisudski had made a number of evasive statements, but he had never stated explicitly his views on Poland's eastern borders or the political structures he envisioned for the region.

Preliminary Hostilities

Polish revolutionary armed forces were organized in Russia beginning in late 1917. In October 1918, they were merged into the Western Rifle Division. In the summer of 1918, a short-lived Polish communist administration was established in Moscow, led by Stefan Heltman. Both the military and civilian systems were designed to make it easier for communism to be introduced into Poland in the form of a Polish Soviet Republic.

Polish Self-Defense had been created in autumn 1918 around important concentrations of Polish people, such as Minsk, Vilnius, and Grodno, given the precarious situation arising from the retreat of German forces from Belarus and Lithuania and the projected entrance of the Red Army there. They were based on the Polish Military Organisation and were acknowledged as part of the Polish Armed Forces by a decree issued on December 7, 1918 by Polish Chief of State Pisudski.

On November 15, the German Soldatenrat of Ober Ost announced that its authority in Vilnius would be handed over to the Red Army.

The Polish 4th Rifle Division fought the Red Army in Russia in late October 1918. The division was under the command of General Józef Haller of the Polish Army in France. Politically, the division fought under the command of the Polish National Committee (KNP), which was recognized by the Allies as Poland's interim government. The 4th Rifle Division joined the Polish Army in January 1919, thanks to Pisudski's decision.

The Soviets defeated the Polish Self-Defense troops in a number of areas. On December 11, 1918, the Russian Western Army captured Minsk. On December 31, the Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia was established. On 5 January 1919, the Self-Defense troops retreated from Vilnius after three days of severe battle with the Western Rifle Division. Skirmishes between Poland and the Soviet Union resumed in January and February.

The Polish armed forces were thrown together in a hurry to fight in a series of border wars. In February 1919, the Russian front was manned by two large formations: the northern, directed by General Wacaw Iwaszkiewicz-Rudoszaski, and the southern, led by General Antoni Listowski.

Polish–Ukrainian War

The Ukrainian National Council was founded on October 18, 1918, in eastern Galicia, which was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and was commanded by Yevhen Petrushevych. In November 1918, a Ukrainian state was declared there, called as the West Ukrainian People's Republic, with Lviv as its capital. The Ukrainian efforts failed to get the backing of the Entente nations due to Russia-related political factors.

On October 31, 1918, the Ukrainians captured key structures in Lviv. On November 1, the city's Polish citizens launched a counter-offensive, igniting the Polish–Ukrainian War. Since November 22, Lviv has been under Polish administration. The Polish claim to Lviv and eastern Galicia was unmistakable to Polish officials; in April 1919, the Legislative Sejm unanimously proclaimed that Poland should absorb all of Galicia. General Józef Haller's Polish Blue Army landed from France in April and June 1919. It was made up of about 67,000 men who were well-equipped and well-trained. The Blue Army contributed significantly to the war's result by assisting in driving Ukrainian soldiers east past the Zbruch River. By mid-July, the West Ukrainian People's Republic had been crushed, and eastern Galicia had been taken over by Poland. The fall of the West Ukrainian Republic strengthened many Ukrainians' conviction that Poland was their country's principal adversary.

From January 1919, conflict erupted in Volhynia, as Poles fought Ukrainian People's Republic soldiers led by Symon Petliura. The Polish onslaught resulted in the province's western half being taken seized. The Polish–Ukrainian conflict there ended in late May, and an armistice was signed in early September.

The Allied Supreme War Council mandated Polish sovereignty over eastern Galicia for 25 years on November 21, 1919, after difficult debates, with pledges of autonomy for the Ukrainian population. In March 1923, the Conference of Ambassadors, which succeeded the Supreme War Council, accepted Poland's claim to eastern Galicia.

Polish Intelligence

Jan Kowalewski, a polyglot and amateur cryptographer, cracked the codes and ciphers of General Anton Denikin's White Russian forces and the army of the West Ukrainian People's Republic. He was appointed chief of the Polish General Staff's cryptography unit in Warsaw in August 1919. By early September, he had recruited a team of mathematicians from the Universities of Warsaw and Lviv (including the founders of the Polish School of Mathematics, Stanisaw Leniewski, Stefan Mazurkiewicz, and Wacaw Sierpiski), who had also cracked the Soviet Russian ciphers. During the Polish–Soviet War, the deciphering of Red Army radio transmissions by the Poles allowed them to effectively utilize Polish military forces against Soviet Russian forces, winning numerous individual engagements, including the Battle of Warsaw.

Early Progression of the Conflict

The Red Army seized Vilnius on January 5, 1919, resulting in the founding of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia (Litbel) on February 28. On February 10, Soviet Russia's People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin wrote to Polish Prime Minister Ignacy Paderewski, proposing that the two countries resolve their differences and establish relations. It was part of a series of notes that the two administrations exchanged in 1918 and 1919.

The new Polish parliament stated the need to liberate "the northeast regions of Poland with their capital in Wilno" in February, as Polish soldiers marched east to fight the Soviets. The Battle of Bereza Kartuska, a Polish–Soviet skirmish, took place after German World War I troops were evacuated from the region. It happened at Byaroza, Belarus, during a local Polish offensive effort led by General Antoni Listowski from the 13th to the 16th of February. The event has been described as the start of a liberation war by the Poles or a campaign of aggression by the Russians against the Poles. The Soviet westward push had come to a halt by late February. The Polish soldiers crossed the Neman River, captured Pinsk on 5 March, and reached the outskirts of Lida while the low-level battle continued; on 4 March, Pisudski ordered further push to the east to be halted. The Soviet leadership was focused with giving military aid to the Hungarian Soviet Republic as well as the White Army's Siberian operation, directed by Alexander Kolchak.

By July 1919, Polish soldiers had defeated the West Ukrainian People's Republic in the Polish–Ukrainian War. Pisudski was able to redeploy part of the forces employed in Ukraine to the northern front in early April, while secretly planning an assault on Soviet-held Vilnius. The goal was to produce a foregone conclusion and prevent Western powers from awarding the White Movement's Russia the territory claimed by Poland (the Whites were expected to prevail in the Russian Civil War).

On April 16, a second Polish onslaught began. Pisudski commanded a force of 5,000 men towards Vilnius. As they advanced east, the Polish forces captured Lida on April 17, Novogrudok on April 18, Baranavichy on April 19, and Grodno on April 28. Pisudski's forces arrived in Vilnius on April 19 and took control of the city after two days of battle. The Litbel administration was driven from its declared capital by the Polish operation.

On the 22nd of April, Pisudski published a "Proclamation to the inhabitants of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania" in support of his federation goals. It was roundly attacked by Pisudski's opponents, the National Democrats, who demanded direct Polish incorporation of the old Grand Duchy lands and declared their opposition to Pisudski's territorial and political ideas. Pisudski had so proceeded to militarily restore the traditional Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth territories, deferring the required political decisions until later.

On April 25, Lenin issued an order to the commander of the Western Front to retake Vilnius as quickly as possible. Between 30 April and 7 May, the Red Army formations that attacked the Polish soldiers were beaten by Edward Rydz-units. migy's While the Poles expanded their gains, the Red Army withdrew from their strongholds, unable to achieve its objectives and faced increased battle with White forces elsewhere.

On May 15, the Polish "Lithuanian–Belarusian Front" was formed under the command of General Stanisaw Szeptycki.

The Polish Sejm, in a statute passed on May 15, asked for the integration of the eastern boundary nations as independent entities in the Polish state. It was meant to leave a good impression on the attendees of the Paris Peace Conference. Ignacy Paderewski, Poland's Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, expressed Poland's support for eastern states' self-determination at the conference, in keeping with Woodrow Wilson's ideology and in an attempt to obtain Western support for Poland's policy in Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania.

Because of the strong chance of Poland's war with Germany over territorial and other concerns, the Polish attack was halted near the line of German trenches and fortifications from World War I. By the middle of June, half of Poland's military forces had been concentrated on the German front. Following the Treaty of Versailles, the offensive in the east was restarted at the end of June. Germany signed and approved the treaty, which maintained the status quo in western Poland.

In May and July, on the southern front in Volhynia, Polish soldiers clashed with the Red Army, which was forcing Petliura's Ukrainian units out of the contested regions. The Polish rulers were despised by the rural Orthodox people, who openly supported the Bolsheviks. The Polish soldiers continued to advance to the east in Podolia and near the eastern limits of Galicia until December. They crossed the Zbruch River and drove Soviet forces out of several towns.

On August 8, Polish forces captured Minsk. On August 18, the Berezina River was reached. The town of Babruysk was conquered for the first time on August 28th, when tanks were deployed for the first time. Polish forces had reached the Daugava River by September 2nd. On September 10th, Barysaw was seized, and on September 21st, parts of Polotsk were taken. The Poles had seized the region along the Daugava from the Dysna River to Daugavpils by mid-September. The lines had also stretched south, cutting through Polesia and Volhynia, and reaching the Romanian border along the Zbruch River. As the line indicated by Pisudski as the goal of the Polish campaign in the north was reached, a Red Army attack between the Daugava and Berezina Rivers was repelled in October, and the front had become relatively dormant with only intermittent clashes.

The Sejm voted in October 1919 to merge the seized lands up to the Daugava and Berezina Rivers, including Minsk, into Poland.

The Polish victories in July 1919 were due to the Soviets prioritizing the White forces' warfare, which was more important to them. The victories gave the impression of Polish military might and Soviet weakness. "I am not concerned about Russia's strength; if I wanted to, I could go now, say to Moscow, and no one would be able to oppose my authority...", Pisudski said. Because Pisudski did not want to help the strategic situation of the advancing Whites, he halted the offensive in late summer.

The White movement had taken the lead in early summer 1919, and its forces, led by Anton Denikin and known as the Volunteer Army, marched on Moscow. Because he saw the Whites as a greater threat to Poland than the Bolsheviks, Pisuski declined to join the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. Pisudski had an acrimonious connection with tsarist Russia from the beginning of his career. From the beginning of his time as Polish commander-in-chief, he was at odds with Soviet Russia. He misjudged the Bolsheviks' might based on this experience. Pisudski also believed that the Bolsheviks could negotiate a better deal for Poland than the Whites, who, in his perspective, represented old Russian imperial policies antagonistic to a strong Poland and an independent Ukraine, which were Pisudski's principal goals. The Bolsheviks considered the partitions of Poland to be illegitimate and stated their support for the Polish people's right to self-determination. Pisudski argued that the internationalist Bolsheviks, who were also estranged from Western powers, would be a better fit for Poland than the reconstituted Russian Empire, its traditional nationalism, and its alliance with Western politics. By refusing to join the attack on Lenin's faltering administration, he defied tremendous Triple Entente pressure and rescued the Bolshevik government in the summer and fall of 1919, despite the fact that a full-scale offensive by Poles to help Denikin would have been impossible. [91] Later, Mikhail Tukhachevsky predicted that if the Polish government cooperated militarily with Denikin during his approach on Moscow, it would be devastating for the Bolsheviks. Denikin afterwards released a book in which he portrayed Poland as the Bolshevik power's savior.

Denikin sought Pisudski's assistance again, in the summer and autumn of 1919. "The defeat of Russia's south will force Poland to confront a power that will be a tragedy for Polish culture and threaten the existence of the Polish state," Denikin claims. Pisudski claims that "Facilitating the defeat of White Russia by Red Russia is the lesser evil.... We fight for Poland with any Russia. We're not going to be pulled into and utilized in the war against the Russian revolution, no matter how dirty the West is. On the contrary, we want to make it easier for the revolutionary army to fight the counter-revolutionary army in the service of long-term Polish interests." The Red Army drove Denikin out of Kiev on December 12th.

Poland's and White Russia's self-perceived objectives were incompatible. Pisudski desired to dismantle Russia and establish a great Poland. Denikin, Alexander Kolchak, and Nikolai Yudenich fought for the "one, mighty, and indivisible Russia's" territorial integrity. Pisudski despised the Bolshevik military forces and considered Red Russia to be easily defeated. The communists who had won the civil war would be pushed far east and deprived of Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic regions, and the southern Caucasus; they would no longer be a menace to Poland.

Many peace proposals were announced by both the Polish and Russian sides from the start of the conflict, but they were merely cover or stalling tactics as each side focused on military preparations and operations. After the summer 1919 wartime activity ended, a series of Polish-Soviet negotiations began in Biaowiea and were relocated to Mikashevichy in early November 1919. Ignacy Boerner, a Pisudski associate, met there with Julian Marchlewski, Lenin's messenger. The Soviet authorities, buoyed by their soldiers' victories in the Russian Civil War, rejected the harsh Polish armistice conditions in December. Two days after the Soviet capture of Kiev, Pisudski ended the Mikashevichy discussions, although serious military actions had not resumed. Boerner notified Marchlewski early in the discussions that Poland had no intention of restarting its onslaught, allowing the Soviets to deploy 43,000 troops from the Polish front to battle Denikin.

The winter onslaught on Daugavpils was the lone exception to Poland's policy of front stabilization since autumn 1919. Previous attempts by Edward Rydz-migy to seize the city in the summer and early autumn had failed. On December 30, representatives of Poland and the Latvian Provisional Government signed a secret political and military contract proposing a joint attack on Daugavpils. Polish and Latvian forces (30,000 Poles and 10,000 Latvians) launched a coordinated offensive against the unexpected enemy on 3 January 1920. The Bolshevik 15th Army withdrew without being pursued, and the conflict ended on January 25th. The 3rd Legions Infantry Division, led by Rydz-migy, was principally responsible for the capture of Daugavpils. The town and its environs were then given up to the Latvians. The campaign's conclusion hampered communication between Lithuanian and Russian forces. Until July 1920, a Polish garrison was stationed in Daugavpils. Simultaneously, Latvian officials pursued peace talks with the Soviets, culminating in the signing of a preliminary armistice. Pisudski and the Polish diplomatic corps were not informed of the development and were unaware of it.

The battle in 1919 resulted in the establishment of an extremely lengthy frontline, which favored Poland at the time, according to historian Eugeniusz Duraczyski.

Pisudski began his mammoth task of dismantling Russia and forming the Intermarium group of countries in late 1919 and early 1920. Given Lithuania's and other eastern Baltic countries' rejection to engage in the initiative, Putin turned his attention to Ukraine.

Abortive Peace Process

Many Polish politicians believed that by late October 1919, Poland had attained strategically favorable eastern borders, and that fighting the Bolsheviks should be ended and peace discussions should begin. Popular feelings were dominated by the quest of peace, and anti-war demonstrations were held.

Soviet Russia's government was dealing with a variety of critical domestic and external issues at the time. To effectively address the problems, they intended to put an end to the fighting and give peace to their neighbors, in the hopes of escaping the worldwide isolation they had been subjected to. Potential allies of Poland (Lithuania, Latvia, Romania, or the South Caucasus states) were unwilling to join a Polish-led anti-Soviet alliance since they were courted by the Soviets. Faced with waning revolutionary fervor across Europe, the Soviets were tempted to postpone their flagship ambition, a Soviet republic of Europe, indefinitely.

Russia's Foreign Secretary Georgy Chicherin and other Russian political institutions submitted peace offers to Warsaw between late December 1919 and early February 1920, but they were ignored. The Soviets recommended a troop demarcation line that was beneficial to Poland and coincided with present military frontiers, deferring permanent boundary judgments until later.

While the Soviet overtures piqued the interest of the socialist, agrarian, and nationalist political camps, the Polish Sejm's attempts to prevent additional combat proved ineffective. Józef Pisudski, who oversaw the military and, to a large extent, the weak civilian government, stymied any attempts at peace. He urged the Polish delegation to engage in phony negotiations with the Soviets by late February. Pisudski and his associates emphasized what they viewed as the Polish military superiority over the Red Army growing over time, as well as their belief that the state of war had provided extremely advantageous conditions for Poland's economic development.

General Wadysaw Sikorski launched a new offensive in Polesia on March 4, 1920, when Polish forces drove a wedge between Soviet forces to the north (Belarus) and south (Poland) (Ukraine). In Polesia and Volhynia, the Soviet counter-offensive was beaten back.

The March 1920 peace talks between Poland and Russia had no results. Pisudski had no desire for a peaceful resolution to the war. Preparations for a large-scale resumption of hostilities were nearing completion, and the newly declared marshal and his circle expected the planned fresh offensive to bring Pisudski's federalist views to fruition (despite the protests of a majority of parliamentary deputies).

Chicherin accused Poland of rejecting the Soviet peace offer on April 7th, and informed the Allies of the alarming developments, pressing them to intervene to avoid Polish violence. Polish diplomacy claimed that countering the urgent threat of a Soviet assault in Belarus was necessary, but Western opinion, which found the Soviet arguments to be legitimate, dismissed the Polish story. On the Belarusian front, Soviet forces were weak at the moment, and the Bolsheviks had no plans for an offensive move.

Piłsudski's Alliance with Petliura

Pisudski was able to work on a Polish–Ukrainian alliance against Russia after resolving Poland's armed problems with the developing Ukrainian governments to Poland's satisfaction. Andriy Livytskyi and other Ukrainian ambassadors expressed their willingness to give up Ukrainian claims to eastern Galicia and western Volhynia in exchange for Poland's recognition of the Ukrainian People's Republic's independence on December 2, 1919. (UPR). On April 21, 1920, Pisudski signed the Treaty of Warsaw, which included an agreement with Hetman Symon Petliura, an exiled Ukrainian nationalist leader, and two other members of the Directorate of Ukraine. It appeared to be Pisudski's breakthrough, indicating the start of a successful application of his long-held ideas. Petliura, who ostensibly represented the Ukrainian People's Republic government, which had been de facto destroyed by the Bolsheviks, fled to Poland with some Ukrainian forces, where he obtained political refuge. Only a sliver of ground near the Polish-controlled areas was under his authority. Petliura had no choice but to accept the Polish offer of alliance, which was largely based on Polish demands, as established by the conclusion of the two nations' recent conflict.

Petliura recognized the Polish territorial advances in western Ukraine and the future Polish–Ukrainian border along the Zbruch River by reaching an agreement with Pisudski. He was offered Ukrainian independence in exchange for surrendering Ukrainian territorial claims, as well as Polish military support in restoring his government in Kiev. Because of the strong hostility to Pisudski's eastern policy in war-torn Poland, the negotiations with Petliura were held in secret, and the content of the 21 April agreement was kept hidden. Ukraine's right to territories of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (before 1772) east of the Zbruch was recognized by Poland. On April 24, a military convention was enacted, placing Ukrainian units under Polish authority. A trade deal between Poland and Ukraine was negotiated by May 1st. It had not been signed to avoid its far-reaching clauses, which foreshadowed Poland's exploitation of Ukraine, from being revealed and wreaking havoc on Petliura's political reputation.

The alliance provided Pisudski with an actual starting point for his Intermarium federation campaign, as well as the potential most important federation partner. It also met his demands for parts of Poland's eastern border relevant to the proposed Ukrainian state, and laid the groundwork for a Polish-dominated Ukrainian state between Russia and Poland.

While Petliura could not add substantial power to the Polish invasion, the alliance provided some camouflage for Pisudski's "naked hostility involved," according to Richard K. Debo. Despite his acceptance of the loss of West Ukrainian regions to Poland, it was Petliura's last chance to preserve Ukrainian statehood and at least a notional independence of the Ukrainian heartlands.

The UPR was not recognized by the British and French, who blocked its entry to the League of Nations in October 1920. Poland received no foreign help as a result of the contract with the Ukrainian republic. It sparked fresh tensions and confrontations, particularly among Ukrainian nationalist movements seeking independence.

Both leaders faced stiff criticism in their respective countries over the agreement they had reached. Roman Dmowski's National Democrats, who opposed Ukrainian independence, fought Pisudski hard. Stanisaw Grabski resigned as chairman of the foreign affairs committee in the Polish parliament, where the National Democrats were a powerful force, to oppose the alliance and the looming war over Ukraine (their approval would be needed to finalize any future political settlement). Many Ukrainian politicians chastised Petliura for signing a peace treaty with the Poles and abandoning western Ukraine (which they saw as occupied by Poland after the fall of the West Ukrainian People's Republic).

Polish officials engaged in forced requisitions, some of which were intended for troop supplies, as well as significant theft of Ukraine and its people, while occupying the territory designated for the UPR. It ranged from high-level sanctioned and promoted acts, such as the mass robbery of trains loaded with commodities, to pillage committed by Polish soldiers in Ukrainian countryside and cities. In letters to General Kazimierz Sosnkowski and Prime Minister Leopold Skulski dated April 29 and May 1, Pisudski highlighted that the railroad loot was massive, but he couldn't say more because the appropriations were made in violation of Poland's contract with Ukraine.

At the start of the Kiev campaign, the alliance with Petliura provided Poland with 15,000 allied Ukrainian forces, which grew to 35,000 through recruiting and Soviet deserters during the conflict. According to Chwalba, the original onslaught involved 60,000 Polish soldiers and 4,000 Ukrainians; but, as of September 1, 1920, there were only 22,488 Ukrainian soldiers on the Polish food ration list.

Polish Forces

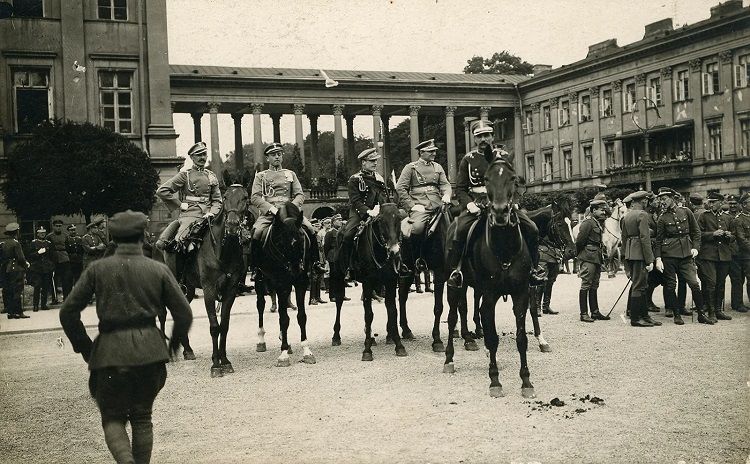

Soldiers who had served in the armies of the dividing empires (particularly professional officers), as well as many new enlistees and volunteers, made up the Polish Army. Soldiers from various militaries, units, origins, and traditions were there. While veterans of Pisudski's Polish Legions and the Polish Military Organisation occupied a privileged position, merging the Greater Poland Army and the Polish Army from France into the national military posed numerous problems. The unification of the Greater Poland Army, led by General Józef Dowbor-Municki (a highly regarded force of 120,000 soldiers), and the Polish Army from France, led by General Józef Haller, with the main Polish Army, led by Józef Pisudski, was completed in a symbolic ceremony on October 19, 1919 in Kraków.

Many factions opposed conscription in the new Polish state, whose survival was in doubt. For various reasons, Polish peasants and small-town dwellers, Jews, and Ukrainians from Polish-controlled territory, for example, tended to avoid duty in the Polish armed forces. The Polish military was almost entirely made up of ethnic Poles who were devout Catholics. The growing problem of desertion in summer 1920 prompted the imposition of the death penalty for desertion in August. The executions and summary military trials were frequently held on the same day.

The Voluntary Legion of Women was made up of female soldiers who were usually assigned to auxiliary jobs. With the assistance of the French Military Mission in Poland, a system of military training for commanders and troops was constructed.

The Polish Air Force possessed roughly 2,000 planes, most of which were elderly. They had been taken by the enemy in 45 percent of cases. At any given moment, only two hundred people might be in the air. They were used for a variety of objectives, including fighting, but the majority of the time they were utilized for reconnaissance. As part of the French Mission, 150 French pilots and navigators flew.

According to Norman Davies, assessing the strength of enemy forces is difficult, and even generals' reports of their own forces are sometimes incomplete.

By the conclusion of 1918, the Polish army had grown to over 500,000 men in early 1920, and 800,000 by the spring of that year. The army had a total strength of around one million soldiers, including 100,000 volunteers, before the Battle of Warsaw.

Military personnel from Western missions, particularly the French Military Mission, helped the Polish armed forces. In addition to the allied Ukrainian forces (about 20,000 soldiers), Russia and Belarusian battalions, as well as volunteers of all ethnicities, aided Poland. The Kociuszko Squadron had twenty American pilots. Their efforts to the Ukrainian front in the spring and summer of 1920 were seen as crucial.

On the Polish side, Russian anti-Bolshevik forces fought. In the summer of 1919, about a thousand White soldiers fought. The Russian Political Committee, represented by Boris Savinkov, supported the largest Russian unit, which was headed by General Boris Permikin. The "3rd Russian Army" grew to over ten thousand battle-ready soldiers and was despatched to the front in early October 1920 to fight on the Polish side; but, due to the armistice in force at the time, they did not engage in combat. From May 31, 1920, 6,000 soldiers fought heroically on the Polish side in Russian "Cossack" units. In 1919 and 1920, a number of minor Belarusian formations battled. The Russian, Cossack, and Belarusian military formations, on the other hand, had their own political goals, and their participation in the Polish war narrative has been neglected or eliminated.

Due to Soviet casualties and the spontaneous registration of Polish volunteers, the two armies were roughly equal in size; by the Battle of Warsaw, the Poles may have gained a tiny numerical and logistical advantage. The First Polish Army was one of the most important forces on the Polish side.

Red Army

Lenin and Leon Trotsky started rebuilding the Russian military forces in early 1918. On 28 January, the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) founded the new Red Army to replace the demobilized Imperial Russian Army. On March 13, Trotsky was appointed commissar of war, and Georgy Chicherin took up Trotsky's previous position as foreign minister. The Commissar Bureau was established on April 18th, and it was this bureau that began the practice of assigning political commissars to military formations. One million German soldiers controlled the western Russian Empire, but Lenin authorized general conscription on October 1st, after the first signs of German loss in the west, with the goal of forming a multi-million-member army. While over 50,000 former tsarist officers joined the White Volunteer Army, by summer 1919, 75,000 had joined the Bolshevik Red Army.

In September 1918, the Russian Republic's Revolutionary Military Council was founded. Trotsky presided over the meeting. Trotsky lacked military experience and expertise, but he knew how to rally troops and was a master of propaganda during wartime. Revolutionary war councils for certain fronts and armies were subordinated to the republic's council. The system was designed to put the concept of communal leadership and control of military matters into practice.

Sergey Kamenev, the Red Army's chief commander from July 1919, was appointed by Joseph Stalin. Former tsarist generals led Kamenev's Field Staff. The Military Council had to approve every choice he made. Trotsky employed an armored train to go around the front regions and coordinate military action, and the actual command center was established in it.

Hundreds of thousands of Red Army recruits deserted, leading to 600 public executions in the second half of 1919. The army, on the other hand, carried out operations on multiple fronts and remained a capable combat force.

On August 1, 1920, the Red Army had a total of five million soldiers, but only 10 to 12 percent of them could be considered active combatants. In Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army, female volunteers fought alongside men on an equal footing. Logistics, supply, and communication were particularly weak points for the Red Army. The White and Allied troops had acquired large quantities of Western armaments, and local military equipment manufacture continued to rise throughout the war. Even still, the stocks were frequently dangerously short. Boots were in poor supply, as they were in the Polish Army, and many soldiers fought barefoot. Because there were so few Soviet planes (220 at most on the Western Front)[136], Polish air formations quickly began to dominate the skies.

The Russian Southwestern Front had roughly 83,000 Soviet men, including 29,000 front-line troops, when the Poles launched their Kiev Offensive. The Poles enjoyed a numerical advantage of between 12,000 and 52,000 men. On all fronts, the Soviets numbered around 790,000 during the Soviet counter-offensive in mid-1920, at least 50,000 more than the Poles. Mikhail Tukhachevsky claimed to have 160,000 combat-ready troops, whereas Pisudski assessed Tukhachevsky's forces to be between 200,000 and 220,000.

According to Davies, the Red Army had 402,000 soldiers on the Soviet Western Front and 355,000 on the Southwestern Front in Galicia in 1920. Between July and August, Grigori F. Krivosheev assigns 382,071 men to the Western Front and 282,507 to the Southwestern Front.

There were no separate Polish units within the Red Army after the restructuring of the Western Rifle Division in mid-1919. Aside from Russian divisions, there had been independent Ukrainian, Latvian, and German–Hungarian units on both the Western and Southwestern Fronts. Furthermore, many communists of diverse ethnicities, such as Chinese communists, fought in combined groups. To some extent, the Lithuanian Army backed the Soviet forces.

Semyon Budyonny, Leon Trotsky, Sergey Kamenev, Mikhail Tukhachevsky (the new commander of the Western Front), Alexander Yegorov (the new commander of the Southwestern Front), and Hayk Bzhishkyan were among the commanders spearheading the Red Army advance.

Logistics and Plans

Both armies struggled with logistics, relying on whatever equipment was left behind from World War I or could be captured. For example, the Polish Army utilized firearms from five distinct countries and rifles from six different countries, all of which used different ammunition. During the Russian Civil War, the Soviets had extensive military depots left by German armies following their retreat in 1918–1919, as well as sophisticated French munitions obtained in large numbers from the White Russians and Allied expeditionary forces. Despite this, they faced a weapons scarcity, since both the Red Army and Polish forces were woefully underequipped by Western standards.

The Red Army, on the other hand, had a huge armory and a fully operational weaponry manufacture in Tula, both inherited from tsarist Russia. There were no weapon factories in Poland, therefore everything had to be imported, including guns and ammunition. Gradual progress had been made in the field of military manufacture, and after the war, Poland had 140 industrial units producing military equipment.

The Polish–Soviet war was fought using agile units rather than trench warfare. The complete front ran about 1500 kilometers (nearly 900 miles) and was manned by a modest number of troops. The Soviets had extremely long transportation links at the time of the Battle of Warsaw and had been unable to supply their men in a timely manner.

The Red Army had been quite successful against the White movement by early 1920. The Soviets began concentrating forces on the Polish northern front, along the Berezina River, in January 1920. The Soviet Union's Baltic Sea embargo was lifted by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. On 3 February, Estonia and Russia signed the Treaty of Tartu, recognizing the Bolshevik government. European arms merchants continued to furnish the Soviets with military supplies, which the Russian government paid for with gold and valuables confiscated from imperial stock and taken from individuals.

Both the Polish and Soviet sides had been preparing for significant battles since early 1920. However, Lenin and Trotsky had not yet been able to eliminate all of the White forces approaching them from the south, particularly Pyotr Wrangel's army. Without such restrictions, Pisudski was able to attack first. He resolved to deal with the last enemy, the Bolsheviks, after concluding that the Whites were no longer a threat to Poland. The Kiev Expedition's goal was to defeat the Red Army on Poland's southern border and install the pro-Polish Petliura regime in Ukraine.

Victor Sebestyen, the author of a 2017 Lenin biography, wrote: "The conflict was launched by the newly independent Poles. In March 1920, they invaded Ukraine with the help of England and France." Former British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, who labeled the Kiev Expedition "a simply aggressive endeavor, a wanton enterprise," was among those who did not support Poland. Pisudski was described by Sebestyen as a "Polish nationalist, not a socialist."

Kiev Offensive

The Polish General Staff ordered the armed forces to take up offensive positions on April 17, 1920. The Red Army, which had been reorganizing since March 10, was not yet fully prepared for battle. The military operation's principal purpose was to establish a Ukrainian state that would be legally independent but backed by Poland and remove Poland from Russia.

The southern group of Polish soldiers, led by Pisudski, launched an offensive in the direction of Kiev on April 25. Thousands of Ukrainian soldiers under Petliura, who represented the Ukrainian People's Republic, aided the Polish army.

The 12th and 14th Armies were available to Alexander Yegorov, commander of the Russian Southwestern Front. They met the invading force, but they were tiny (15,000 battle-ready soldiers), weak, and ill-equipped, and their attention had been diverted by peasant uprisings in Russia. Since the Soviets learned of Poland's war preparations, Yegorov's armies had been steadily reinforced.

"The Polish Army would only stay as long as required until a legal Ukrainian government took authority over its own land," Pisudski said in his "Call to the People of Ukraine" on April 26. Many Ukrainians were anti-communist, but they were also anti-Polish and despised the Polish expansion.

In Ukraine, the well-equipped and highly mobile Polish 3rd Army, led by Edward Rydz-migy, rapidly defeated the Red Army. The Soviet 12th and 14th Armies withdrew or were driven past the Dnieper River after refusing to engage in action for the most part and suffering just minor losses. On the 7th of May, the combined Polish–Ukrainian forces headed by Rydz-migy found only minor resistance when they reached Kiev, which had been largely abandoned by the Soviet military.

Using the Western Front forces, the Soviets launched their initial counteroffensive. Mikhail Tukhachevsky launched an offensive on the Belarusian front on Leon Trotsky's orders, ahead of the (scheduled by the Polish command) arrival of Polish forces from the Ukrainian front. His forces attacked the inferior Polish armies there on 14 May, penetrating the Polish-held territory (territories between the Daugava and Berezina Rivers) to a depth of 100 kilometers. From 28 May, Stanisaw Szeptycki, Kazimierz Sosnkowski, and Leonard Skierski spearheaded a Polish counteroffensive after two Polish divisions came from Ukraine and the new Reserve Army was established. As a result, Poland was able to reclaim the majority of the lost area. The front had steadied at the Avuta River on June 8 and remained dormant until July.

From the 29th of May, the Polish drive into Ukraine was met with Red Army counterattacks. Yegorov's Southwestern Front had been significantly reinforced at that time, and he launched an assault maneuver in the Kiev area.

On June 5, Semyon Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army (Konarmia) launched a series of attacks that shattered the Polish–Ukrainian front. To disrupt the Polish rearguard and threaten communications and logistics, the Soviets deployed mobile cavalry battalions. The Polish soldiers were retreating throughout the whole front by the 10th of June. General Rydz-migy, with the Polish and Ukrainian soldiers under his command, followed Pisudski's orders and surrendered Kiev to the Red Army (despite the fact that the city was not under attack).

Soviet Victories

On April 29, 1920, the Bolshevik Communist Party of Russia's Central Committee issued a call for volunteers for the war with Poland, in order to defend the Russian republic against a Polish usurper. On May 6, the volunteer army's first regiments left Moscow for the front lines. The Soviet publication Pravda published an article on May 9th ""Go West!" (Russian: a аад!): "The route to the World Inferno lies via the corpse of White Poland. We will convey happiness and peace to laboring humanity on bayonets ".. General Aleksei Brusilov, the final tsarist commander-in-chief, wrote an appeal "To all former commanders, wherever they may be" in Pravda on 30 May 1920, urging them to forgive past grievances and join the Red Army. All Russian officers, according to Brusilov, had a patriotic responsibility to join the Bolshevik government, which he believed was defending Russia against foreign invaders. Lenin recognized the significance of appealing to Russian nationality. Brusilov's engagement aided the Soviet Russia counteroffensive: 14,000 officers and over 100,000 lower-ranking soldiers recruited or returned to the Red Army; thousands of citizen volunteers also contributed to the war effort.

The 3rd Army and other Polish troops managed to escape devastation during their long retreat from the Kiev border, but remained stranded in western Ukraine. They were unable to bolster the Polish northern front and boost the Avuta River defenses, as intended by Pisudski.

With no strategic reserves, Poland's 320 km (200 mi) long northern front was manned by a thin line of 120,000 infantry backed by 460 artillery pieces. This method of retaining position was similar to the technique of creating a constructed line of defense during World War I. The Polish–Soviet front, on the other hand, was poorly staffed, supported by inferior artillery, and had essentially no fortifications, bearing little similarity to the conditions of that battle. The Soviets were able to gain numerical dominance in vital locations as a result of this arrangement.

The Red Army collected its Western Front against the Polish line, led by the young General Mikhail Tukhachevsky. It had about 108,000 men and 11,000 cavalry, with 722 artillery pieces and 2,913 machine guns to back them up.

Tukhachevsky's 3rd, 4th, 15th, and 16th Armies, according to Chwalba, had a total of 270,000 soldiers and a 3:1 advantage over the Poles on the Western Front's attack area.

On the 4th of July, a more powerful and well-prepared Soviet second northern attack was started along the Smolensk–Brest axis, crossing the Avuta and Berezina Rivers. The 3rd Cavalry Corps, sometimes known as the "attack army" and led by Hayk Bzhishkyan, played a significant role. The Polish first and second lines of defense were overcome on the first day of action, and on July 5, the Polish forces began a full and rapid retreat throughout the whole front. During the first week of action, the combat strength of the First Polish Army was decimated by 46%. The retreat quickly devolved into a disorderly and chaotic escape.

Lithuania began talks with the Soviets on July 9th. The Lithuanians launched a series of raids on the Poles, disrupting the Polish forces' planned transfer. On July 11, Polish troops withdrew from Minsk.

Only Lida was defended for two days along the line of old German trenches and fortifications from World War I. On July 14, Bzhishkyan's army, along with Lithuanian forces, took Vilnius. Budyonny's cavalry approached Brody, Lviv, and Zamo from the south, in eastern Galicia. The Poles had realized that the Soviet goals were not confined to mitigating the impact of the Kiev Expedition, but that Poland's independence was on the line.

The Soviet soldiers advanced westward at breakneck speed. Bzhishkyan's 3rd Cavalry Corps conquered Grodno on July 19 in a daring maneuver; on July 27, Bzhishkyan's 3rd Cavalry Corps captured the strategically vital and easy-to-defend Osowiec Fortress. On the 28th of July, Biaystok fell, and on the 29th of July, Brest. The sudden collapse of Brest prevented a Polish counteroffensive that Pisudski had planned. The Polish high command attempted to defend the Bug River line, which the Russians had reached on 30 July, but Pisudski's plans were canceled due to the swift loss of the Brest Fortress. The Western Front was only around 100 kilometers (62 miles) from Warsaw after crossing the Narew River on August 2.

However, at that time, Polish resistance had grown stronger. Because of the close proximity to Polish population centers and the surge of volunteers, the reduced front allowed for greater concentrations of Polish troops engaged in defensive actions. Polish supply lines had become overburdened, while enemy logistics had gotten overburdened. General Sosnkowski was able to recruit and activate 170,000 additional Polish soldiers in just a few weeks, but Tukhachevsky stated that instead of completing their task as fast as they had hoped, his force was met with fierce resistance.

Polish forces were forced out of much of Ukraine by the Southwestern Front. Sergey Kamenev's orders were blocked by Stalin, who commanded Budyonny's units to shut in on Zamo and Lviv, the major city in eastern Galicia and the garrison of the Polish 6th Army. In July 1920, the long-running Battle of Lviv began. Stalin's conduct harmed Tukhachevsky's forces in the north, because Tukhachevsky required aid from Budyonny, near Warsaw, where critical engagements were fought in August. Rather than launching a coordinated attack on Warsaw, the two Soviet fronts drifted apart. On the 16th of August, during the Battle of Warsaw, Pisudski seized the resulting void to launch his counteroffensive.

The Polish forces attempted to stop Budyonny's advance on Lviv during the Battle of Brody and Berestechko (29 July–3 August), but the effort was thwarted by Pisudski, who mustered two divisions to fight for the Polish capital.

The Polish and Soviet delegates met in Baranavichy on August 1, 1920, and exchanged notes, but their armistice talks had no results.

Diplomatic Front

Although the Western Allies were critical of Polish politics and dissatisfied with Poland's refusal to cooperate with the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War, they nevertheless supported the Polish forces fighting the Red Army, shipping armaments, extending credits, and providing political support. France was particularly dissatisfied, but also keen to combat the Bolsheviks, so Poland was an obvious ally in this regard. On the Polish–Russian problem, British politicians had a wide range of viewpoints, although many were harshly critical of Polish policies and actions. The US Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker, accused Poland of practicing imperial politics at the expense of Russia in January 1920. Irritated by Polish behavior, the Allies considered transferring the regions east of the Bug River to Allied rule under the auspices of the League of Nations in early April 1920.

In the autumn of 1919, Prime Minister David Lloyd George's British administration agreed to deliver weaponry to Poland. Following the Polish annexation of Kiev on May 17, 1920, the cabinet spokesman declared in the House of Commons that "no help has been or will be offered to the Polish government."

The initial success of the Kiev Expedition prompted widespread enthusiasm in Poland, and most politicians recognized Pisudski's leadership role. As the tide turned against Poland, Pisudski's political power waned, while that of his opponents, such as Roman Dmowski, grew. In early June, Pisudski's ally Leopold Skulski's cabinet resigned. On June 23, 1920, an extra-parliamentary government led by Wadysaw Grabski was appointed after protracted wrangling.

The Western Allies were concerned about the Bolshevik armies' progress, but they blamed Poland for the situation. According to them, Polish leaders' actions were daring and amounted to stupidly playing with fire. It has the potential to derail the work of the Paris Peace Conference. Peace and good relations with Russia were desired by Western societies.

The Soviet leadership's confidence grew as the Soviet armies advanced. Lenin cried in a telegram, "All of our efforts must be focused on preparing and strengthening the Western Front. Prepare for war with Poland, according to a new slogan ".. In an article for the journal Pravda, Soviet communist theorist Nikolai Bukharin expressed his desire for resources to take the battle beyond Warsaw, "right up to London and Paris." General Tukhachevsky's advice is as follows: "The road to global conflagration leads through the cadaver of White Poland... on to... Warsaw! Forward!" As victory became increasingly certain, Stalin and Trotsky became embroiled in political intrigues and squabbled over the course of the main Soviet onslaught.

Jews were subjected to antisemitic violence by Polish soldiers during the height of the Polish–Soviet struggle, who saw them as a possible threat and frequently accused them of helping the Bolsheviks. Ydokomuna charges fueled the perpetrators of the pogroms that occurred. Polish authorities detained Jewish soldiers and volunteers during the Battle of Warsaw and transported them to an incarceration camp.]

To meet the immediate Soviet danger, Poland's national resources were quickly mobilized, and rival political forces pledged their allegiance. The State Council of Defense was established on July 1st. On the 6th of July, Pisudski was defeated in the council, prompting Prime Minister Grabski to travel to the Spa Conference in Belgium to seek Allied help and mediation in opening up peace talks with Soviet Russia. As a prerequisite for their participation, the Allied representatives made a number of demands. On July 10, Grabski signed an agreement with the Allies that included the following terms: Polish forces would withdraw to the border intended to demarcate Poland's eastern ethnographic frontier and published by the Allies on December 8, 1919; Poland would participate in a subsequent peace conference; and the Allies would decide on the sovereignty over Vilnius, Eastern Galicia, Cieszyn Silesia, and Danzig. In exchange, the Allies promised to assist in settling the Polish–Soviet war.

George Curzon, the British Foreign Secretary, sent a telegram to Georgy Chicherin on July 11, 1920. It asked the Soviets to cease their attack at the Curzon Line (along the Bug and San Rivers) and accept it as a temporary border with Poland until a permanent border could be established through discussions. It was suggested that talks with Poland and the Baltic states take place in London. The British threatened to aid Poland with undefined means if the Soviets refused. Poland's "loss was greater than the Poles had thought," according to Roman Dmowski. Chicherin rejected British mediation and stated his willingness to negotiate directly with Poland in a Soviet answer delivered on July 17th. Both the British and the French responded by making more firm vows to assist Poland with military weapons.

The Communist International's Second Congress met in Moscow from July 19 to August 7, 1920. The delegates avidly followed daily dispatches from the front as Lenin talked of the increasingly favorable odds for the success of the World Proletarian Revolution, which would lead to the World Soviet Republic. Workers from all nations were urged to oppose their governments' efforts to aid "White" Poland, according to the conference.

The administration dispatched a team to Moscow on July 22 to request armistice talks after Pisudski lost another vote in the Defense Council. The Soviets claimed to be exclusively interested in peace talks, which the Polish delegation was not allowed to address.

The Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee (Polrewkom), backed by the Soviets, was established on July 23 to organize the administration of Polish territory gained by the Red Army. Julian Marchlewski led the committee, which also included Feliks Dzieryski and Józef Unszlicht. In the Soviet-controlled Poland, they had little backing. The Polrewkom decreed the end of the Polish "gentry–bourgeoisie" administration on July 30 in Biaystok. Mikhail Tukhachevsky received Polrewkom's representatives at the Biaystok rally on 2 August on behalf of Soviet Russia, the Bolshevik party, and the Red Army. On July 8, the Galician Revolutionary Committee (Galrewkom) was formed.

The Polish Government of National Defense, led by Wincenty Witos and Ignacy Daszyski, was founded on July 24. It immediately embraced a dramatic land reform program designed to counter Bolshevik propaganda (the scope of the promised reform was greatly reduced once the Soviet threat had receded). The government attempted to hold peace talks with Soviet Russia, and on August 5, a new Polish delegation attempted to cross the front and make contact with the Soviets. General Kazimierz Sosnkowski was appointed Minister of Military Affairs on August 9.

Politicians ranging from Dmowski to Witos were harsh in their criticism of Pisudski. His military aptitude and judgment were called into doubt, and he showed evidence of mental illness. However, a majority of members of the Council of National Defense, which Pisudski had requested to rule on his fitness to lead the military, promptly voiced their "complete confidence." Dmowski quit his council membership and left Warsaw, disillusioned.

When Czechoslovak and German workers refused to transport such materials to Poland, sabotage and delays in delivery of war supplies occurred. Following a consultation with the British government, British official and Allied representative Reginald Tower deployed his soldiers to offload supplies bound for Poland after the 24 July strike of harbour employees in Gdask. On August 6, the British Labour Party published a booklet stating that British workers would not fight alongside Poland in the war. In its daily L'Humanité, the French section of the Workers' International declared: "For conservative and capitalist Poland, he is not a man, a sou, or a shell. The Russian Revolution will live on! Long live the Internationale des Travailleurs! ".. The transit of supplies destined for Poland through Germany, Austria, and Belgium was prohibited. The Polish government released a "Appeal to the World" on August 6, disputing accusations of Polish imperialism and emphasizing Poland's confidence in self-determination as well as the perils of a Bolshevik invasion of Europe.

Hungary offered to deploy a 30,000-strong cavalry army to Poland's aid, but Czechoslovak President Tomá Masaryk and Foreign Minister Edvard Bene were opposed to helping Poland, and the Czechoslovak government refused to let them through. Czechoslovakia proclaimed neutrality in the Polish–Soviet War on August 9, 1920. Hungary delivered significant volumes of military and other desperately needed supplies to Poland. In September 1920, the prominent Polish general Tadeusz Rozwadowski said of the Hungarians, "You were the only nation that truly wished to help us."

On August 8, the Soviets presented the Allies with their armistice conditions in Britain. Sergey Kamenev promised that the Soviet Union would recognize Poland's independence and right to self-determination, but his conditions amounted to demands for the Polish state's submission. Prime Minister David Lloyd George and the British House of Commons endorsed the Soviet demands as equitable and reasonable, and the British envoy in Warsaw gave Foreign Minister Eustachy Sapieha unambiguous advice on the subject. The Polish team arrived to Tukhachevsky's offices in Minsk on August 14 for the official peace talks. Georgy Chicherin presented them with severe peace conditions on August 17th. On the outskirts of Warsaw, decisive fighting were already taking place. The majority of foreign delegations and Allied missions had left Warsaw for Pozna.

Lithuania was embroiled in territorial disputes and armed clashes with Poland over the city of Vilnius and the surrounding districts of Sejny and Suwaki in the summer of 1919. The attempt by Pisudski to seize control of Lithuania by staging a coup in August 1919 exacerbated the deterioration of relations. On July 12, 1920, the Soviet and Lithuanian governments signed the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty, which recognized Vilnius and its surrounding areas as portions of a projected Greater Lithuania. The contract had a hidden clause allowing Soviet forces unlimited mobility in Lithuania during any Soviet war with Poland, raising concerns about Lithuania's neutrality during the current Polish–Soviet War. The Lithuanians also supplied logistical support to the Soviets. The Red Army held Vilnius after the treaty was signed, and the Soviets returned it to Lithuanian authority shortly before it was regained by Polish forces in late August. When the Soviets won the war with Poland, they supported their own communist government, the Litbel, and planned a Soviet-backed Lithuanian administration. The Soviet–Lithuanian Treaty was a Soviet diplomatic win and a Polish defeat; it destabilized Poland's domestic politics, as Russian ambassador Adolph Joffe warned.

In 1919, the French Military Mission to Poland landed with 400 members. It was primarily made up of French officers, with a few British advisers led by Adrian Carton de Wiart. The mission, led by General Paul Prosper Henrys, included a thousand officers and men in July 1920. Members of the French Mission contributed to the fighting preparation of Polish forces through their training programs and frontline involvement. Captain Charles de Gaulle was among the French officers. He was awarded the Virtuti Militari, Poland's highest military decoration, during the Polish–Soviet War. De Gaulle had joined General Józef Haller's "Blue Army" in France. France sponsored the army's transit to Poland in 1919. The Blue Army was largely made up of Poles, although there were also international volunteers who had served under French command during World War I. France was hesitant to assist Poland in its conflict with Soviet Russia in 1920. Only after the Soviet armistice conditions were given on August 8th did France proclaim, through its representative in Warsaw, its commitment to support Poland in its fight for independence morally, politically, and materially.

The extended Interallied Mission to Poland landed in Warsaw on July 25, 1920. It consisted of British diplomat Edgar Vincent, French diplomat Jean Jules Jusserand, and Maxime Weygand, chief of staff to Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the victorious Entente's overall commander. With Weygand as the war's main military commander, Allied politicians were anticipated to take control of Poland's foreign affairs and military strategies. It was not permitted, and General Weygand accepted a position as an advisor. [196] The sending of the Allied mission to Warsaw demonstrated that the West had not abandoned Poland, giving Poles hope that all was not lost. The mission members contributed significantly to the war effort. The important Battle of Warsaw, on the other hand, was fought and won exclusively by Poles. Many people in the West mistakenly felt that the timely arrival of the Allies had saved Poland; Weygand played a key role in the illusion that was established.

French hardware, including infantry armament, artillery, and Renault FT tanks, were sent to Poland to strengthen its military as the Polish–French cooperation continued. France and Poland signed a formal military partnership on February 21, 1921. The Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs dedicated special emphasis during the Soviet–Polish discussions to keeping the Allies informed of their progress and having them feel accountable for the outcome.

The Soviet priority had steadily changed away from fostering international revolution and toward demolishing the Pact of Versailles system, which Lenin referred to as the "triumphant world imperialism treaty." During the Russian Communist Party RKP(b9th )'s Conference, held on September 22–25, 1920, Lenin made remarks to that effect. He made numerous references to the Soviet military defeat, for which he tacitly blamed himself for a considerable part. Stalin and Trotsky held each other responsible for the war's fate. Stalin slammed Lenin's claims about Stalin's judgment leading up to the Battle of Warsaw. The seizure of Warsaw, while not very significant in and of itself, would have allowed the Soviets to smash the Versailles European system, according to Lenin.

Before the Battle

On the 20th of July 1920, the commander-in-chief of the Red Army, Sergey Kamenev, devised a plan in which two Soviet fronts, Western and Southwestern, would launch a concentric attack on Warsaw. After speaking with Tukhachevsky, the Western Front commander, Kamenev believed that the seizure of Warsaw could be handled by the Western Front alone.

Tukhachevsky's goal was to annihilate the Polish soldiers in the Warsaw region. One of his armies was to attack the Polish capital from the east, while three others were to make their way north over the Vistula, between Modlin and Toru. Parts of this arrangement were to be employed to outflank Warsaw on the western flank. On August 8, he issued orders to such effect. Tukhachevsky quickly realized that his designs were not yielding the anticipated results.