The history of syphilis is as intriguing as it is complex, marked by a fascinating pattern of blame-shifting among nations. When syphilis first emerged in Europe in the late 15th century, it quickly became a subject of international finger-pointing, with each country attributing the disease to its neighbors or perceived adversaries. This pattern of assigning blame reflects not only the fear and confusion surrounding the disease but also the geopolitical tensions of the time.

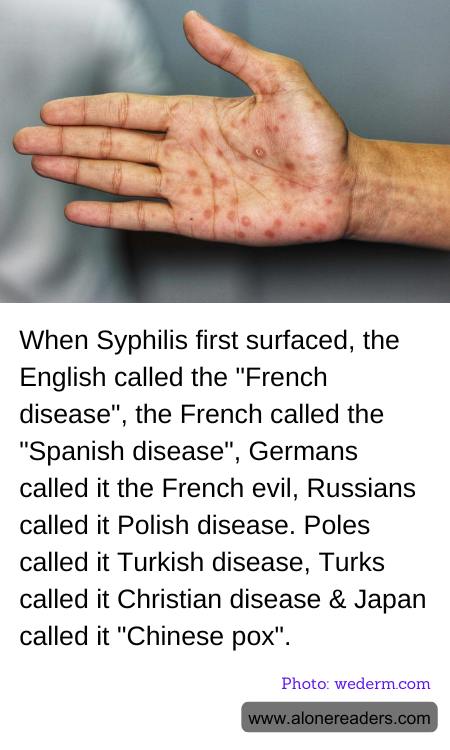

In England, syphilis was dubbed the "French disease," a term that underscored the longstanding rivalry and animosity between the English and the French. The French, in turn, referred to it as the "Spanish disease," likely due to the political and military conflicts with Spain. This pattern continued across Europe, with Germans calling it the "French evil," while Russians labeled it the "Polish disease." The Poles, not to be outdone, referred to it as the "Turkish disease," reflecting the historical conflicts with the Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile, the Turks called it the "Christian disease," a term that highlighted the religious and cultural divides of the era. Even in Asia, the blame game persisted, with Japan referring to syphilis as "Chinese pox."

This pattern of naming reveals much about the social and political dynamics of the time. Diseases were often seen as foreign invaders, much like enemy armies, and naming them after rival nations was a way to externalize the threat and avoid internal blame. This practice also highlights the lack of understanding about the disease's origins and transmission, as well as the absence of effective medical treatments. In an era before modern medicine, diseases were often shrouded in mystery, and attributing them to outsiders was a way to cope with the fear and uncertainty they brought.

The naming conventions also reflect the broader context of nationalism and xenophobia that characterized much of European history. By associating a disease with a rival nation, countries could reinforce negative stereotypes and justify political or military actions against them. This practice of naming diseases after other countries has persisted into modern times, as seen with various pandemics and outbreaks, illustrating how deeply ingrained these patterns are in human behavior.

Despite the historical blame game, syphilis is now understood as a bacterial infection caused by Treponema pallidum, transmitted primarily through sexual contact. Advances in medicine have demystified the disease, allowing for effective treatments and prevention strategies. However, the legacy of its naming serves as a reminder of how fear and prejudice can shape our understanding of health and disease. As we continue to face global health challenges, it is crucial to approach them with a spirit of cooperation and understanding, rather than division and blame.