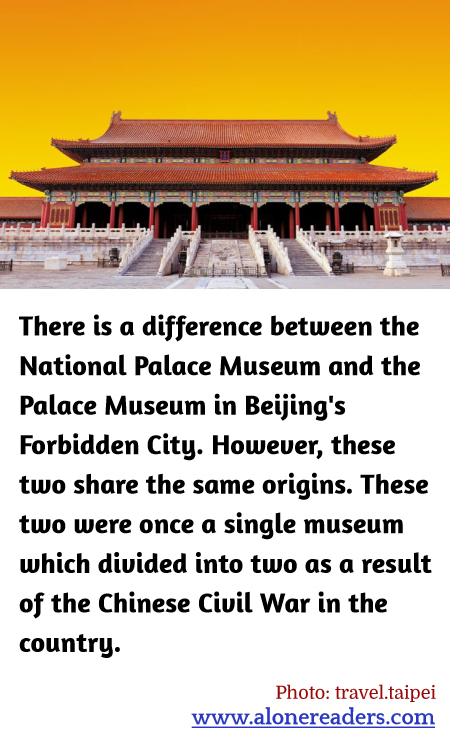

The National Palace Museum in Taipei and the Palace Museum located in Beijing's Forbidden City are two landmark institutions with shared historical roots, yet they have very distinct identities today. Originally both were part of the same establishment, housing an extensive collection of artifacts amassed by China's emperors over centuries. The origins of this split trace back to the tumultuous period of the Chinese Civil War.

In the early 20th century, after the fall of China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing Dynasty, the Palace Museum was established in 1925 within the walls of the newly opened Forbidden City. It was an effort to preserve the immense wealth of cultural heritage that had accumulated in the imperial palaces. However, the outbreak of the Chinese Civil War necessitated urgent measures to protect these invaluable artifacts from the hazards of war and potential looting.

When the conflict intensified, the government of the Republic of China decided to move the most valuable pieces of the collection. Initially, these treasures were transported to various locations within China for safekeeping. Eventually, in 1947, as the Communist Party gained control over mainland China, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government relocated the bulk of the collection to Taiwan. This move was intended to be temporary; however, the subsequent victory of the Communists in 1949 made this relocation permanent.

The establishment of the National Palace Museum in Taipei in 1965 was aimed at continuing the preservation and display of these relocated collections. Over the years, the museum in Taipei has become a cultural beacon, showcasing one of the world’s largest collections of Chinese art and artifacts spanning nearly 8,000 years. These include ancient paintings, imperial documents, ceremonial regalia, and antiquities that reflect the rich tapestry of Chinese history.

On the other hand, the Palace Museum in Beijing remains in its original location in the Forbidden City, a grand imperial palace that served as the home of emperors and their households, as well as the ceremonial and political center of Chinese government for almost 500 years. Despite the separation of the collections, the Beijing museum also holds a formidable assortment of art and historical relics, and it stands as a symbol of China’s imperial past, drawing millions of visitors annually.

Thus, while both museums originate from the same roots and share the goal of preserving and showcasing Chinese heritage and culture, they are shaped by their unique historical journeys and geopolitical realities. The division of their collections is a poignant reminder of the wider historical and political schism that altered the course of Chinese history in the mid-20th century. Today, each museum offers a unique perspective on the rich, multifaceted narrative of Chinese civilization.