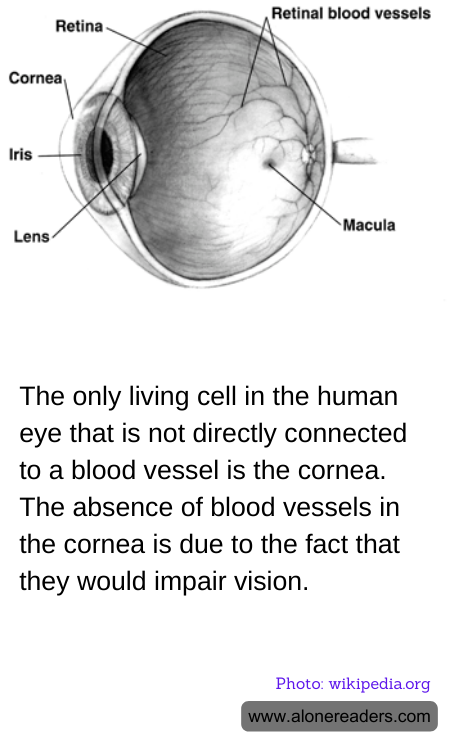

The human eye is a marvel of biological engineering, and one of its most unique features is the cornea. Located at the very front of the eye, the cornea serves as the eye's clear, protective outer layer. Unlike other cells in the human body, the cells in the cornea are quite unique because they do not have a direct blood supply. This lack of direct blood vessel connection is crucial for maintaining clear vision.

Blood vessels, by their very nature, can obstruct light as it passes through, which could lead to blurred or impaired vision. Therefore, the absence of blood vessels in the cornea is essential for transparency and clarity, which are necessary for optimal vision. Instead of blood vessels, the cornea receives its nutrition from the aqueous humor—the clear, watery fluid that fills the space between the cornea and the lens—and from the tear film that covers the exterior of the eye. Oxygen is also absorbed directly from the air through the tear film, which further contributes to the health and function of corneal cells.

The way the cornea maintains its transparency while still being a live, active tissue is a subject of ongoing research and fascination in the field of ophthalmology and medical science. This clear front window of the eye not only allows light to enter for vision but also plays a significant role in the eye's ability to focus, providing approximately 75% of the eye's focusing power.

Any damage to the cornea can lead to serious complications, affecting both vision and the health of the eye. Conditions such as keratitis, an inflammation of the cornea, or more severe issues like keratoconus, where the cornea thins and begins to bulge outward into a cone shape, can drastically affect vision. Advances in medical technology have led to sophisticated treatments ranging from laser eye surgery to correct refractive errors to corneal transplants for more severe damage.

The cornea’s design highlights an intriguing aspect of evolutionary adaptation, enabling perfect vision through a clear, living window devoid of the vascular network typical to nearly every other part of the human body. This unique adaptation not only allows us to see the world in high clarity and detail but also speaks to the complex interplay of requirements and solutions in biological systems. Such insights continue to inspire both awe and groundbreaking innovations in medical science.