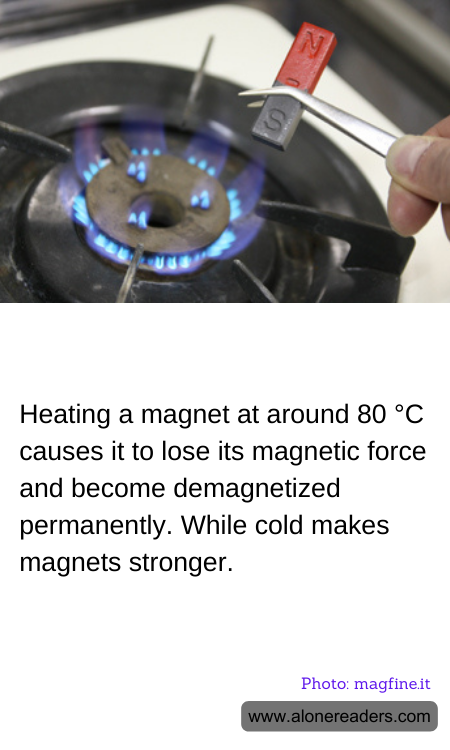

When heated to around 80°C, a magnet can lose its magnetism and become permanently demagnetized. This loss of magnetic force is related to the behavior of atoms within the magnet. Magnets are made up of microscopic regions called domains, which are groups of atoms with magnetic poles aligned in the same direction. At room temperature, these domains maintain their alignment, giving the magnet its magnetic field.

However, as the temperature of the magnet increases, the energy within the atoms increases as well. This added energy causes the atoms to move more vigorously, which can lead to the misalignment of the domains. When the temperature reaches a certain point, known as the Curie temperature, the magnet’s domains become so disordered that the magnet loses its magnetic properties entirely. For many magnets, this point can be around 80°C, though it varies depending on the material of the magnet. Once cooled, the magnet does not regain its original strength, essentially becoming demagnetized permanently.

Conversely, cooling a magnet can increase its magnetic strength. Lower temperatures reduce the thermal energy within the magnet, which allows the domains to align more cohesively. This enhanced alignment strengthens the magnetic field of the magnet. In extremely low temperatures, such as those close to absolute zero, magnets can reach a state of minimal internal energy, where almost all domains are perfectly aligned, yielding the strongest possible magnetic field.

This relationship between temperature and magnetism is critical in various applications and industries. For example, magnetic materials used in electronic devices, motors, and generators must be chosen and designed considering their operating temperature environments to ensure they function efficiently and safely. Moreover, understanding these principles helps in the development of new magnetic materials and in improving the performance of existing ones.

Hence, managing and manipulating the temperature is key to maintaining the desired magnetic properties for practical applications, and this characteristic is a fundamental aspect of material science in the context of magnetism.