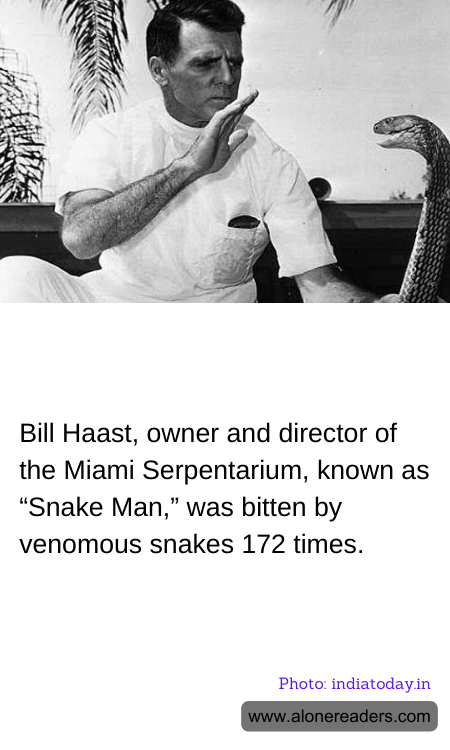

Bill Haast, often hailed as the "Snake Man," led an extraordinary life that intertwined danger and science in the name of medical progress. As the owner and director of the Miami Serpentarium, Haast turned his fascination with snakes into a groundbreaking career that withstood the test of over 100 venomous snake bites—official records suggest he was bitten 172 times. His facility, opened in 1947, was not just a tourist attraction but also a critical site for venomous research and antivenom production.

Haast’s interest in snakes began early, and by the age of 11, he was already extracting venom. This fascination led him, undeterred by the inherent dangers, to a path that would see him become one of the pioneers in venom research. His work was heavily based on the notion that systematic exposure to venom could build immunity—a theory he tested on himself. Over the years, Haast injected himself with diluted venom, a practice that is believed to have saved his life on multiple occasions following venomous bites that would have been fatal to others.

The Miami Serpentarium housed over 500 snakes and attracted thousands of visitors who watched in awe as Haast skillfully extracted venom. The venom was not only sold to research facilities but also provided to pharmaceutical companies for the creation of antivenoms. Beyond his work with snake venom, Haast also contributed to medical studies that explored the potential of venom in treating conditions such as multiple sclerosis and arthritis, displaying a lifelong commitment to unlocking the medical potentials of venom.

In recounting his near-death experiences, Haast’s encounters with snakes like cobras and pit vipers were particularly notable. Despite suffering numerous bites that led to prolonged physical pain, including the loss of a finger and enduring a double heart bypass surgery attributed to a cobra venom, he remained undeterred. He believed firmly in the benefits of his work and maintained a resilience that was as legendary as the snakes he handled.

Bill Haast’s legacy is multifaceted; he was a showman, a scientist, and a survivor. His contributions to herpetology and venom research have had lasting impacts, providing valuable insights and advancements in the production of antivenoms. When he passed away in 2011 at the age of 100, Haast left behind a legacy that was as enduring as his belief in the potential of snake venom to contribute to medical science.