In late 17th century England, a peculiar tax was levied by King William III, known famously as the "window tax." This was a form of property tax that was determined by the number of windows a house possessed. The logic behind this was straightforward yet somewhat arbitrary: the more windows a house had, the wealthier its residents were presumed to be, and therefore, the more they could afford to pay in taxes. This tax was initially introduced in 1696 under the auspices of helping to recover from the financial strains of war and revamping the nation’s fiscal policies.

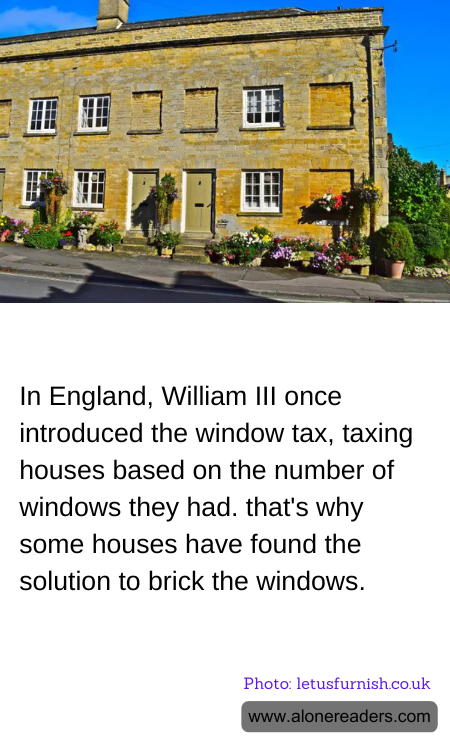

The implementation of the window tax had some unexpected repercussions. To avoid the tax, homeowners began reducing the number of windows in their homes, often going to the extent of bricking up existing windows to decrease their tax liability. This phenomenon became so widespread that it noticeably altered the architecture of the period, with buildings from this era noticeably bearing a lesser number of windows that were typical prior to the introduction of the tax.

This architectural alteration was more than just an aesthetic issue. It had significant health and social impacts. Rooms were dark, and the reduced airflow led to poor ventilation in homes, which in turn contributed to the spread of diseases. The detrimental health effects ultimately led to a public outcry against the window tax. Critics of the tax argued that it was a tax on "light and air," basic necessities that should not be taxed.

The window tax was finally repealed in 1851 after being recognized as a detriment to public health, but the legacy of the tax remained visible in the bricked-up windows of older buildings, a stark reminder of a misguided fiscal measure. Despite its negative aspects, the window tax is an interesting case study in how tax policy can affect architectural practices and public health, and stands as a historical lesson on the unintended consequences of economic decisions.