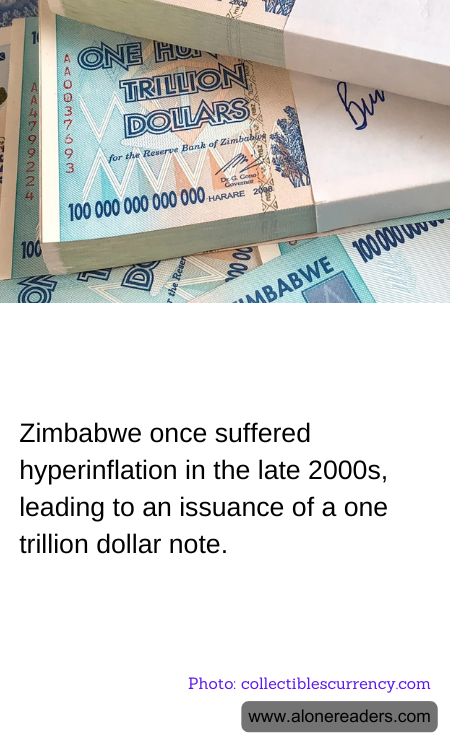

In the late 2000s, Zimbabwe experienced a catastrophic economic crisis characterized by hyperinflation, which became one of the most severe in recorded history. The scale of inflation was so immense that the country eventually issued a one trillion Zimbabwean dollar note in a desperate bid to keep up with the rapidly falling value of their currency.

The roots of Zimbabwe's hyperinflation can be traced back to several key factors. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Zimbabwean government, led by President Robert Mugabe, implemented a series of land reforms that involved the seizure of land from white farmers and redistributing it to Black farmers. However, this process was often carried out violently and without a clear plan for sustaining agricultural productivity. The resulting decline in farm output led to a significant drop in food production and export revenues.

Moreover, the government’s fiscal policies, characterized by excessive money printing, fueled inflation. Initially, this was aimed at financing increased wages for government workers and funding military involvement in the Congo War. The excessive printing of money, alongside declining economic output, led to a loss of confidence in the local currency, which escalated the inflation crisis.

As hyperinflation worsened, everyday life in Zimbabwe became untenably difficult. Prices of basic commodities doubled frequently, sometimes within hours. The rapid devaluation of the Zimbabwean dollar led to scenarios where people needed bags of cash for simple purchases. Even transactions such as buying groceries required amounts of currency that were physically cumbersome to carry. The situation led to a widespread scarcity of goods, and barter trade became increasingly common.

In a bid to keep up with hyperinflation, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe resorted to printing higher and higher denominations of money, culminating in the iconic one trillion dollar note. However, these notes quickly became worthless, and the currency was shunned in favor of foreign currencies like the US dollar and the South African rand.

The situation only stabilized when the government finally abandoned the Zimbabwean dollar in 2009 and officially permitted the use of foreign currencies for all transactions. Although this helped stabilize the economy and brought down inflation, the legacy of hyperinflation has had long-lasting impacts on the country’s economic landscape and has left deep scars on the lives of many Zimbabweans. This period serves as a stark example of how mismanaged economic policies and political instabilities can converge to provoke one of the worst cases of hyperinflation in history.