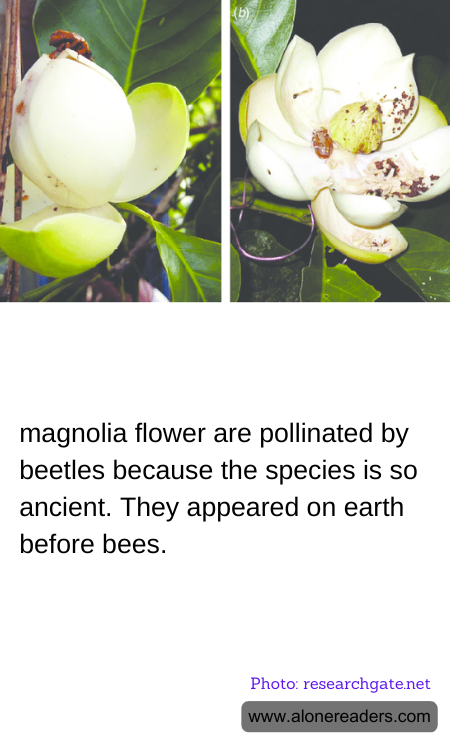

The magnolia flower, with its large and fragrant blossoms, is one of the most ancient flowering plants known to scientists, having appeared long before bees became the predominant pollinators of flowering plants. This timeline has deeply influenced the evolutionary features of the magnolia, particularly its methods of pollination. The magnolia’s thick petals and robust structure are adaptations designed to withstand the more robust manner of its pollinators: the beetles.

Magnolias are believed to date back over 95 million years. During that era, bees had not yet evolved, and plants relied on other insects for pollination. Beetles, which were among the early insects to appear on the scene, played a significant role in this process. Unlike bees, beetles are not nectar seekers by nature; they are typically attracted to a plant for its foliage or flowers, which they consume. The magnolia accommodates these habits by providing a flower structure that supports beetle feeding activities without damage to its reproductive organs.

The relationship between magnolias and their pollinators is a classic example of a coevolutionary link. Magnolia flowers are attractively colored and emit a strong, sweet fragrance that draws beetles in. Their carpels are tough, able to resist damage as beetles chew on parts of the flowers. Meanwhile, as the beetles move around eating and searching for mates, they inadvertently collect pollen on their bodies, transferring it from one flower to another and thus fulfilling their role in the flower’s reproductive cycle.

Interestingly, this ancient method of pollination contrasts substantially with the ways of modern flowering plants, most of which are structured to attract and be pollinated by bees. The evolution of flowering plants alongside bees has typically resulted in changes to flower shapes, colors, and sizes optimizing for bee pollination, which is generally gentler and involves the pursuit of nectar, a substance not produced by magnolias.

The primitive and seemingly crude pollination system of the magnolia highlights not only the complexity of evolutionary adaptations but also the effectiveness of nature's processes. Even as the world around them has changed dramatically, magnolias have persisted relatively unchanged for millions of years, a testament to the lasting success of their natural design. Their continued coexistence with beetles serves as an enduring connection to the ancient past of our planet, offering vital insights into the history of plant and insect development. Today, magnolias and their beetle pollinators remain a key subject of study for evolutionary biologists, ecologists, and botanists, intrigued by this enduring partnership.