In the mid-19th century, the global tea trade was largely dominated by China, the sole source of tea cultivation knowledge and expertise. At this time, Western nations, particularly Britain, were consuming vast amounts of tea but were critically dependent on Chinese tea, which created a significant trade imbalance unfavorably for Britain. In an era marked by empire and industrial revolution, control over such a crucial commodity was a strategic priority.

Enter Robert Fortune, a Scottish botanist, who in 1848 embarked on a daring and covert mission on behalf of the British East India Company. Disguised as a Chinese noble, complete with a long robe, a Qing dynasty-style queue (pigtail), and fluent in Mandarin, Fortune ventured into the remote and closely guarded tea regions of China. This disguise was not only necessary but critical, as these areas were off-limits to foreigners, thus any misstep in his disguise or manners could have led to his discovery and possible imprisonment, or worse.

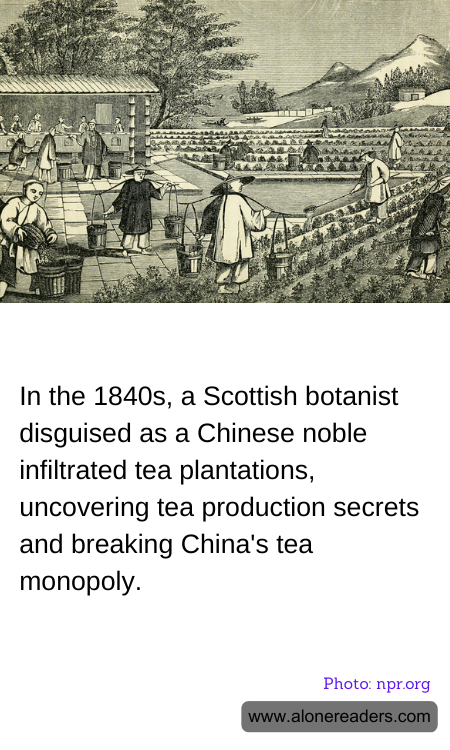

Fortune's mission was to learn everything he could about the cultivation and processing of tea. Over several years, he traveled extensively through China's tea-producing regions, observing and documenting the detailed processes of tea propagation, cultivation, and processing. He collected seeds and cuttings of tea plants, as well as detailed notes on the methods Chinese farmers used to produce their world-renowned teas.

Perhaps more significantly, by the time Fortune returned to Britain, he had shipped numerous cases of tea plants and seeds, as well as a group of experienced Chinese tea workers, to India. These plants and the expertise provided by the Chinese workers who came with them laid the foundations for tea cultivation in British-controlled India, particularly in regions like Darjeeling and Assam, which are now synonymous with tea production. This acted as a pivotal move in breaking the Chinese monopoly on tea, allowing Britain and other Western nations to cultivate tea independently, profoundly reshaping global trade patterns.

The impact of Fortune’s espionage was significant, enabling new colonial enterprises to emerge and altering the balance of economic power in favor of Victorian Britain. It also marked one of the earlier instances of corporate espionage which had lasting implications on global trade. Thus, through his daring and deception, Robert Fortune not only transformed the geographical and economic landscapes of tea production but also changed the course of its global consumption patterns. His adventures blurred the lines between botanical science and political intrigue, highlighting the lengths to which empires would go to control valuable resources.