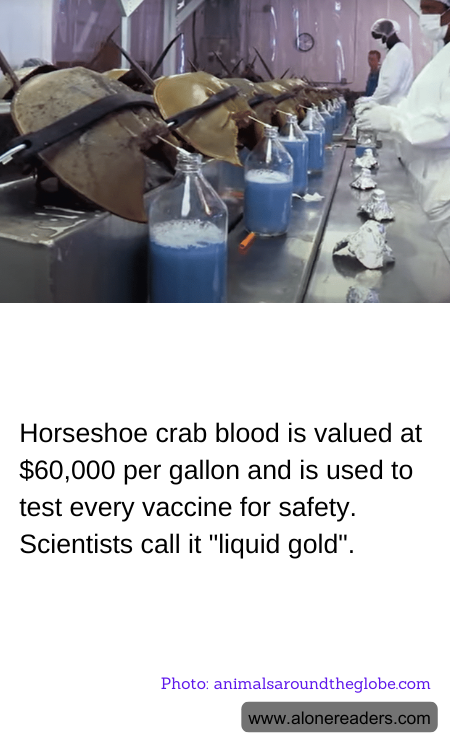

Horseshoe crab blood is indeed one of the medical world's most unlikely yet invaluable resources, earning the moniker "liquid gold" not only for its price—around $60,000 per gallon—but also for its crucial role in modern medicine. This bright blue blood is harvested largely due to its unique properties that are vital in the pharmaceutical industry, especially in the safety testing of vaccines and other injectable drugs.

The blood of horseshoe crabs contains amebocytes, which are cells that play a similar role to the white blood cells in human blood. When these amebocytes encounter pathogens like bacteria, they bind to the invaders and clot, thus helping to isolate and eliminate the infection. This reaction is harnessed in a test known as the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) test, named after the Limulus polyphemus crab species from which the blood is most commonly drawn.

The LAL test is both incredibly sensitive and incredibly valuable because it can detect even trace amounts of bacterial endotoxins. These are components of the outer membrane of certain bacteria that, if present in the bloodstream or in drugs being administered to the body, can lead to reactions, or in severe cases, lethal shock. The sensitivity of the LAL test ensures that pharmaceutical products, including all injectable drugs, implants, and some medically used devices, are safe from these potentially dangerous contaminants.

Despite its significant benefits, the practice of harvesting horseshoe crab blood has raised environmental and ethical concerns. Horseshoe crabs are captured and then approximately 30% of their blood is drawn before they are returned to their habitat. Although many survive the process, a significant percentage do not. The decline in horseshoe crab populations can also adversely affect other species, most notably the red knot, a type of bird that relies on horseshoe crab eggs as a major food source during migration.

In response to these issues, scientists have been diligently working to develop synthetic alternatives to the LAL test. One such alternative, a synthetic version of the essential molecule in horseshoe crab blood, has been approved for use in some areas, though it hasn’t fully replaced the natural LAL test yet. This synthetic substitute not only promises an end to the dependence on horseshoe crab blood but also ensures a more sustainable and less variable resource for medical testing.

As research continues and the pharmaceutical industry leans more towards sustainable practices, the future may see a reduction in the reliance on natural horseshoe crab blood. However, until such alternatives are universally adopted and proven to be as effective, horseshoe crab blood will remain a crucial, though contentious, element in the production of safe medical and pharmaceutical products.