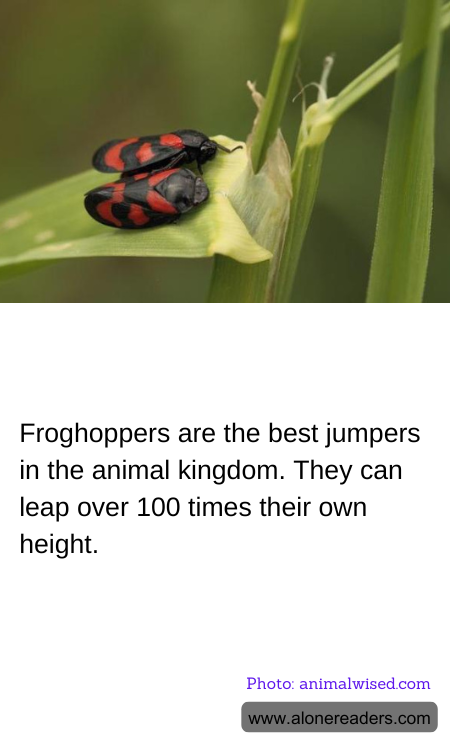

Froghoppers, or spittlebugs as they are sometimes known, hold the record for the highest jumper in the animal kingdom relative to their size. These tiny insects can leap over 100 times their own body height. In comparison, if humans possessed the same ability, we would be able to effortlessly jump over skyscrapers.

The secret to the froghopper's impressive leaping ability lies in its unique physical structure. The insect has specialized hind legs that are designed to handle and store mechanical energy. Before a jump, the froghopper contracts its muscles slowly, building up energy in a structure called the pleural arch, a part of the skeletal frame. This process is akin to pulling back on a slingshot. At the moment of release, this stored energy is unleashed, propelling the froghopper through the air at an incredible speed and distance.

Interestingly, despite their small size, froghoppers undergo this intense physical feat without injury. Their bodies are equipped with internal mechanisms that prevent damage from the rapid acceleration and deceleration associated with their jumps. Moreover, they employ this astounding jump not for feeding or hunting, but primarily as a defense mechanism to escape predators.

The biomechanics of froghopper jumps have intrigued scientists, who continue to study these insects not only to marvel at their natural abilities but also to derive bio-inspired designs. The principles of energy storage and quick release observed in froghoppers are applicable in various technological innovations, including robotic movements and athletic gear design. Thus, understanding the froghopper's jump could possibly lead to advancements in human technology and machinery.

In sum, froghoppers may be small, but their superlative jumping ability is a remarkable feature of the natural world, showcasing the extraordinary outcomes of evolutionary adaptation and biomechanical efficiency.