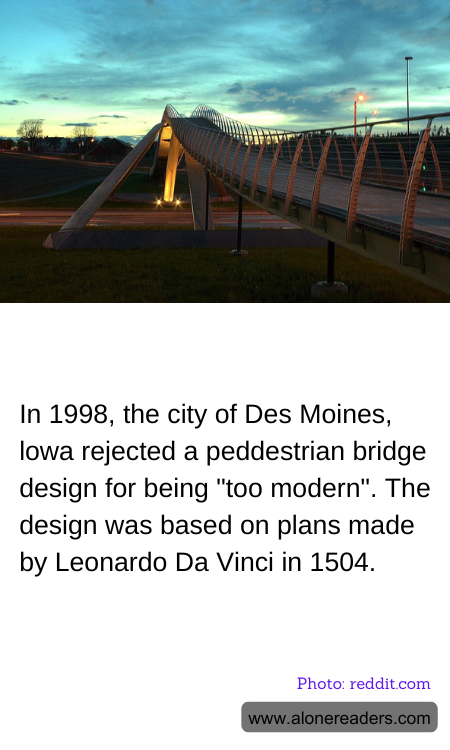

In a surprising blend of past and future, the city of Des Moines, Iowa, faced a unique proposition in 1998 when a pedestrian bridge design was brought to the table. What makes this event notable is that the design was not a product of modern architectural trends, but rather based on sketches by the Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci from the year 1504. Essentially, the bridge that was proposed in Des Moines was intended to be a resurrection of a centuries-old idea, marrying historic design with contemporary urban planning.

Da Vinci, primarily known for his contributions to art and science, was also an inventive engineer. His original bridge design was intended for Sultan Bayezid II of Constantinople as a way to bridge the Golden Horn. It was envisioned as a massive, single-span bridge that was far ahead of its time, primarily due to its unprecedented length and architectural feasibilities during the period it was designed. The bridge was never built in Da Vinci's lifetime, remaining as one of the many ideas he conceptualized that were technologically implausible at the time.

Fast forward nearly five centuries, the city of Des Moines considered this design for a pedestrian bridge that would serve both a functional purpose and as a historical homage. However, despite its intriguing background and potential as a cultural landmark, the proposal was ultimately rejected. The rejection stemmed from concerns regarding the bridge's ultra-modern appearance and how it would fit into the existing cityscape. City planners and some members of the public felt that the design was too avant-garde for the area, clashing with its more traditional aesthetic. This scenario presents a fascinating reflection on how historical designs can interact with modern contexts. It also raises questions about what constitutes 'modern' design and the degrees of historical authenticity and innovation that are acceptable in public architecture.

This case stands out as an encapsulation of a broader discourse on architectural conservatism and the inclusion of historical radical designs in contemporary settings. While the city ultimately did not proceed with Da Vinci's design, the debate it sparked continues to be relevant in architectural and urban planning circles. It underscores the challenges and opportunities that arise when past innovations are brought forward into new eras, offering a platform for discussing how cities can respect their historical context while also embracing bold, new ideas.