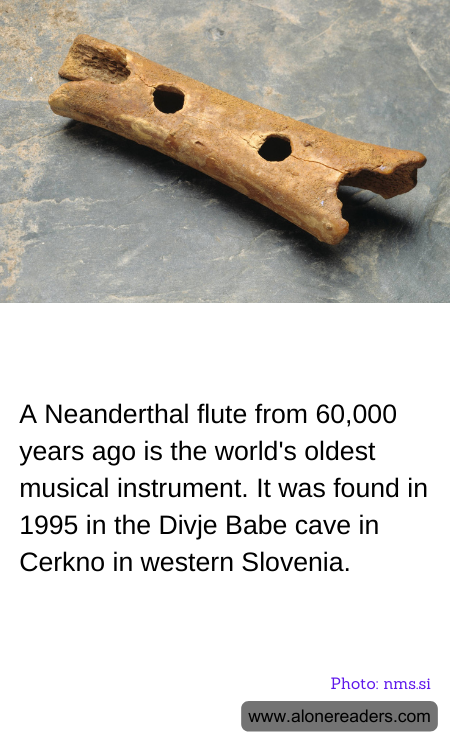

The discovery of a Neanderthal flute at the Divje Babe archaeological site in Slovenia in 1995 added a profound layer to our understanding of prehistoric human culture, suggesting that the origins of music may be much more ancient than previously thought. This artifact, believed to be around 60,000 years old, is considered the world's oldest known musical instrument.

Carved from the femur of a cave bear, the instrument features four to five hole punctures that researchers at the time believed were strategically placed to produce different musical notes. This challenges earlier beliefs that Neanderthals lacked the sophistication required for music creation, indicating instead a society that not only had the capability to think abstractly and artistically but possibly also communicated complex emotions and thoughts.

The implications of such a discovery are vast. The existence of music in the Neanderthal community suggests elements of social rituals or even the potential for language and enhanced cognitive abilities. Ethnomusicologists and archaeologists continue to debate the purpose and use of the flute, with some suggesting that it might have been used in ritualistic practice, while others propose it served a more recreational or communicative function in Neanderthal societies.

This Neanderthal flute not only provides insight into the cognitive abilities of Neanderthals but also paints a richer, more complex picture of their cultural life. With every note it could have produced, the instrument echoes the universality of music as a cross-temporal language of emotion and expression, connecting us intricately with our ancient ancestors. Further studies and findings may continue to shape our understanding of Neanderthals, showing them not just as crude tool-makers but as beings capable of abstract thought, artistic expression, and perhaps even a culture of music reminiscent of our own.