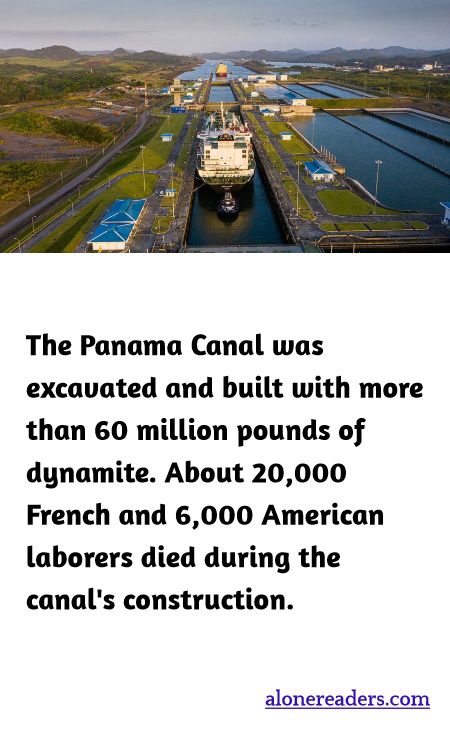

The Panama Canal, often hailed as one of the greatest engineering feats in history, stands as an emblem of human perseverance and technological prowess. However, the construction of this monumental waterway came with immense challenges and at a significant human cost. Completed in 1914, the canal was excavated using more than 60 million pounds of dynamite, highlighting the sheer scale of effort required to sever Central America and join the Atlantic with the Pacific.

Initially undertaken by the French in the 1880s under the leadership of Ferdinand de Lesseps, the project was plagued by problems, including deadly diseases such as malaria and yellow fever, and technical difficulties related to the unsuitable terrain and climate. Unfortunately, an estimated 20,000 workers lost their lives during this phase, underlining the perilous nature of the endeavor.

Subsequent to the French failure, the United States took over the project in 1904, driven by the strategic and commercial benefits the canal would offer. Under the guidance of chief engineer John Frank Stevens and later George Washington Goethals, the U.S. shifted the focus from a sea-level canal to a lock-based system. This decision proved pivotal and ultimately led to the successful completion of the canal. However, the American phase of construction did not occur without further tragic losses, with around 6,000 workers dying, mainly from diseases and accidents.

The completion of the Panama Canal transformed international trade, significantly reducing travel time for shipping between the East and the West coasts of the U.S., and influencing global maritime trade routes. Despite its utility and the transformation it brought, the canal serves also as a somber reminder of the human toll extracted during its construction. The harsh conditions, rampant diseases, and the explosive power harnessed illuminate the complexities and sacrifices embedded in monumental construction achievements.