In the lush rainforests of tropical regions, a particularly sinister parasitic fungus known as Ophiocordyceps unilateralis ensnares a rather unassuming victim, the ant. This fungus has developed a remarkably specialized mechanism of infection that targets, manipulates, and ultimately destroys its host, highlighting a complex interplay of biological control and survival.

Upon infection, the spores of the Ophiocordyceps fungus attach to the exoskeleton of an ant. The fungus then proceeds to infiltrate the host’s body, taking over its neural systems. What unfolds over approximately nine days is a grim spectacle of nature’s manipulation: the fungus integrates itself so thoroughly into the neural circuits of the ant that it gains complete control over the insect’s movements.

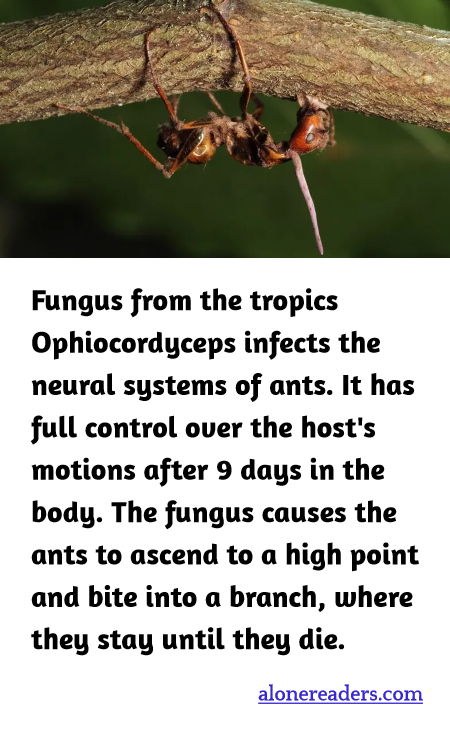

Driven by the parasitic fungus, the ant exhibits unusual behavior, starkly different from its normal functioning. In what could be likened to a zombie-like state, the infected ant leaves its ground-level nest and colleagues, climbing vegetation until it reaches a point that is optimally humid and cool for the fungus’s growth. Here, the ant uses its mandibles to clench onto a leaf or twig in a death grip—a behavior known as the "death bite." Once attached, the ant will remain immobile, eventually dying in this forced perch.

The strategic positioning of the ant is no mere coincidence. By compelling the ant to climb upwards before its demise, the fungus ensures that, upon the ant’s death, the conditions are optimal for its spore dispersal from a height, which maximizes the spread to potential new hosts wandering below. The lifecycle of the fungus culminates as lethal fungal stalks grow from the deceased host, releasing new spores to infect other unsuspecting ants, thus continuing the grim cycle of parasitism.

This phenomenon vividly illustrates one of nature’s more macabre stratagems for survival and propagation. Ophiocordyceps unilateralis goes beyond mere infection; it engineers an intricate and deadly outcome, ensuring its own survival at the lethal expense of the ant. Such instances raise captivating questions about the mechanisms behind such precise biological control and the evolutionary pressures that sculpt them.