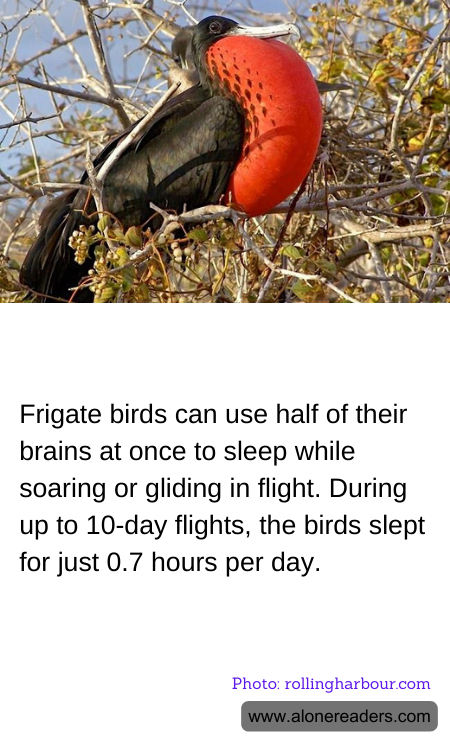

Frigate birds, known for their extraordinary ability to soar and glide on ocean winds for weeks, exhibit a remarkable adaptation that allows them to sleep while flying. These large seabirds can stay aloft for up to 10 days at a time without landing, navigating some of the longest flights in the bird kingdom. During these extensive journeys, frigate birds demonstrate a unique method of sleep: they are capable of sleeping with just one half of their brain at a time, a phenomenon known as unihemispheric slow-wave sleep. This ability is not just limited to frigate birds but is also seen in some aquatic mammals like dolphins, allowing one side of the brain to rest while the other side remains alert.

This extraordinary sleep adaptation is crucial for their survival, as it enables them to remain vigilant to threats and navigate effectively while still getting the rest they need. During a study that followed these birds, it was observed that they only slept about 0.7 hours per day during flight, which is significantly less than their sleep duration when on land. This reduced sleep during flight is sporadic and often occurs in short bursts that last only seconds to a few minutes. Interestingly, while the ability to sleep with half the brain is beneficial during solo flights, these birds are also capable of engaging in bihemispheric sleep, where both halves of the brain are in sleep mode, but this typically happens when they are on land.

This sleep behavior in frigate birds raises intriguing questions about the sleep needs of different species and the potential for sleep flexibility according to environmental demands. It also highlights a fascinating aspect of avian biology that allows these birds to thrive in environments where rest is hard to come by. Their ability to adapt their sleep patterns offers insights into the complex interplay between behavior, physiology, and evolutionary adaptations. This understanding not only broadens our knowledge of avian biology but also contributes to the larger discussion about sleep mechanisms among vertebrates.