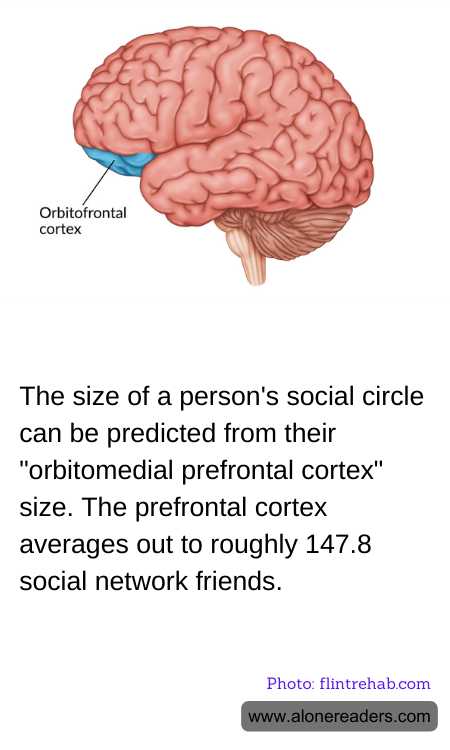

The human brain, with its intricate web of neurons, has long fascinated scientists, particularly in understanding how it influences our social behaviors. Recent studies have zeroed in on the orbitomedial prefrontal cortex (OMPFC), a region that plays a pivotal role in decision-making and social interaction. Interestingly, researchers have found a correlation between the size of this area and the size of an individual's social network. The orbitomedial prefrontal cortex, located just behind the eyes, is crucial for evaluating social information and making emotionally relevant decisions, which are essential for managing complex social networks.

On average, the size of the orbitomedial prefrontal cortex can predict having about 147.8 social network friends. This number intriguingly aligns with the "Dunbar's Number," a theory proposed by anthropologist Robin Dunbar. Dunbar suggested that due to the cognitive limits imposed by the brain, there is an upper limit to the number of stable social relationships a human can maintain, which he capped at about 150 individuals. This finding implies a biological basis for this number, rooted in the neural architecture of the brain.

What's particularly interesting is how this area of the brain may facilitate the management of numerous social connections. The larger the orbitomedial prefrontal cortex, the more capable it may be of handling the complex demands of larger social groups, including keeping track of various emotional states, intentions, and histories of many individuals. This does not necessarily imply that individuals with a smaller OMPFC are less social, but they may have different social dynamics and perhaps maintain closer relationships with fewer people.

This discovery opens new avenues for understanding the neural underpinnings of social behavior and disorders characterized by social deficits, such as autism or social anxiety disorders. It suggests that therapies aimed at enhancing the functioning of the orbitomedial prefrontal cortex could potentially aid in improving social skills in people who find social interactions challenging.

As neuroscience delves deeper into the connections between brain structure and function, the findings underline the profound impact of biology on social behavior. They also reinforce the idea that our social lives are, to a considerable extent, shaped by the biological structures within our brains, providing a fascinating glimpse into the physical foundations of human social interaction. Further research in this area could lead to more targeted interventions designed to enhance or repair social functioning in clinical populations.