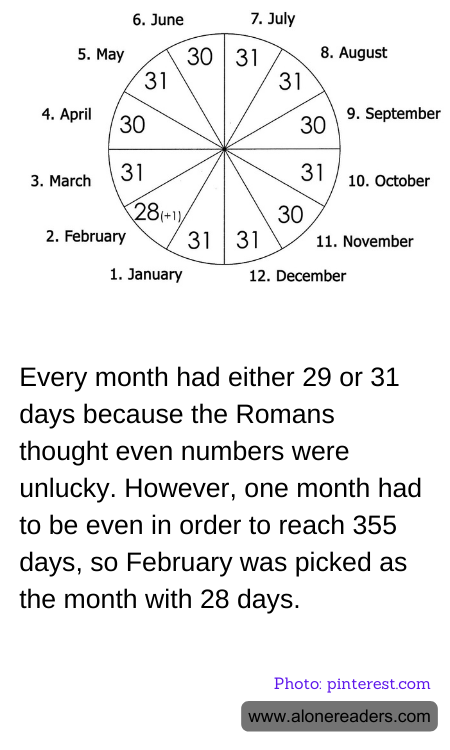

In ancient Rome, superstitions and beliefs significantly influenced the structuring of the calendar. A common Roman superstition was that even numbers were unlucky, which played a pivotal role in the organisation of their lunar calendar. The Romans, aiming to avoid the ill fortune associated with even numbers, designed their months to typically contain odd numbers of days. Remarkably, most months had either 29 or 31 days. The decision behind this uneven distribution was not only rooted in superstition but also a keen emphasis on the auspiciousness of odd numbers, which were believed to bring good fortune and prosperity.

The calendar at that time consisted of 355 days, necessitated by the lunar cycles, which the Roman calendar sought to follow. However, to align with these cycles and reach the total of 355 days, one month had to bear the burden of being even-numbered. February was selected to be that month, primarily because it was already associated with purification and rites of cleansing during the festival of Februa, thus making it somewhat less inauspicious despite its even number of days. Initially set at 28 days, February's length further underscored its role as a month of lesser significance and transitional status within the Roman religious and societal customs.

This structuring led to an imbalance that frequently required adjustments. The Roman high priest, known as the Pontifex Maximus, had the authority to add an extra month every few years to synchronize the calendar with the solar year. This intercalary month, known as Mercedonius, contained 22 or 23 days and was added after February, further emphasizing February’s role as a flexible and adaptable period within the Roman year.

The evolution of the calendar continued when Julius Caesar introduced the Julian calendar in 45 BCE, significantly reforming the structure by incorporating a leap year system and extending the year to 365 days. With these changes, the monthly distribution of days was adjusted, but February retained its 28-day length, only extending to 29 days during leap years. This tradition carried forward into the Gregorian calendar, which is the one most of the world uses today, maintaining February as an outlier in terms of its day count.

Thus, the interplay of superstition, religion, and scientific need shaped the Roman calendar in ways that continue to affect how we organize our days and months even millennia later, with February as a lasting legacy of these ancient practices.