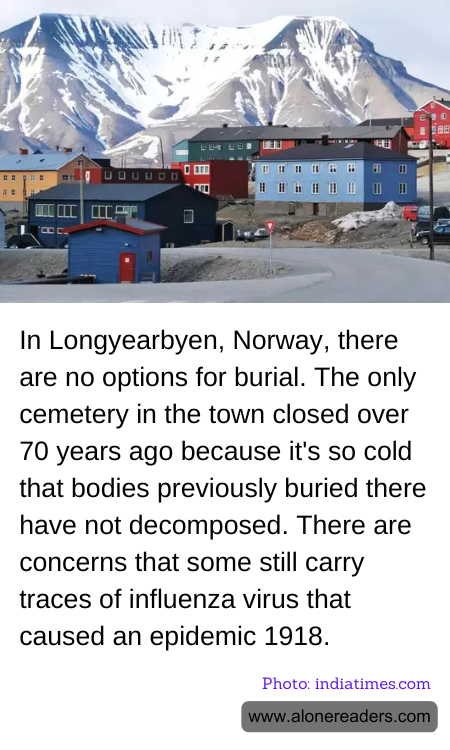

In the remote town of Longyearbyen, Norway, located well within the Arctic Circle, the permafrost and frigid temperatures create a unique and somewhat macabre problem when it comes to dealing with the deceased. The town’s only cemetery closed more than 70 years ago after it was discovered that the permafrost prevented bodies from decomposing. As a result, the buried bodies, instead of decomposing, remained almost mummified, preserved in the icy soil.

This phenomenon posed unexpected risks. Some of the bodies buried in Longyearbyen's cemetery were victims of the 1918 influenza pandemic, commonly known as the Spanish Flu, which swept across the globe, infecting a third of the world's population and resulting in millions of deaths. Scientists have expressed concerns that these bodies might still contain viable strains of the 1918 flu virus. Given the lethal nature of the virus and the potential for it to be released into the environment or potentially infect researchers handling the remains, this presents a unique public health risk.

Due to these risks and the ineffectiveness of ordinary burial methods in such an environment, the residents of Longyearbyen now must send their deceased loved ones to other parts of Norway where the ground is more conducive to decomposition. This practice not only underscores the stark realities of living in such an extreme climate but also impacts the grieving process, as families cannot have their burial sites nearby.

The situation in Longyearbyen serves as a compelling case study of how geography and climate can deeply influence cultural practices – in this case, those surrounding death and burial. It also highlights the broader implications of permafrost thawing due to global warming. As the Earth's climate changes, other regions with permafrost may face similar issues with diseases thought long contained by the cold, posing new challenges for science and public health.