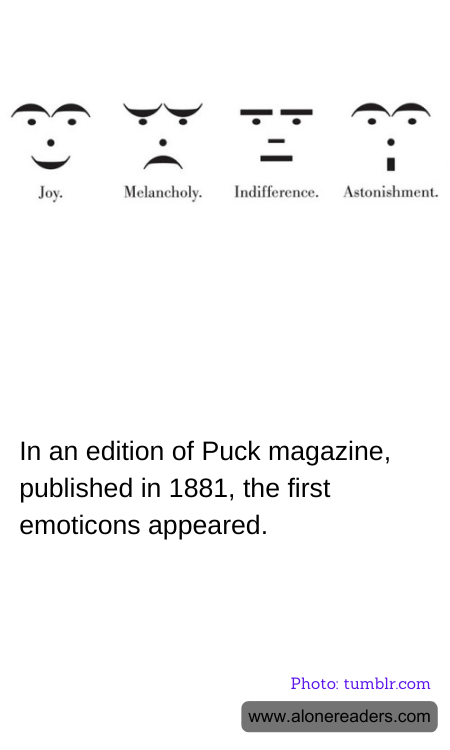

In the rich tapestry of media history, the emergence of emoticons marks a fascinating evolution of language. It is commonly believed that the first use of emoticons, in a form recognizable today, occurred in the 1980s with the advent of digital communication. However, an intriguing predecessor appeared much earlier in Puck magazine, an American humor publication founded in the 1870s. In its March 30, 1881 edition, Puck included a series of typographical emoticons as part of a humorous piece on the joys of typesetters.

This 1881 edition of Puck magazine used simple punctuation marks to craft faces that conveyed emotions, a concept that was both innovative and playful at the time. The characters used were parentheses, semicolons, and brackets, arranged to represent jovial and melancholic expressions—a precursor to the now ubiquitous smiley and frowny faces found in our daily digital dialogues. These early emoticons were part of a satirical article about the pitfalls and pleasures of typography, suggesting that even in the 19th century, there was a recognition of the need to express emotion through text.

This development in Puck is significant not only as a curious artifact but also as an indicator of the period's cultural landscape. The use of such symbols demonstrated an early understanding of the limitations and possibilities of written communication. At a time when long-distance interpersonal communication relied heavily on the written word, these symbols served as forerunners to today’s digital emoticons and emojis, which enrich our ability to convey tone and emotion succinctly.

The pioneering use of emoticons in Puck magazine reminds us that the playfulness in language and the human desire to express emotions through text transcends the digital age, rooting back to the era of print media. Even as modern technology has refined and expanded our use of symbols into a vast array of emojis, the basic premise remains the same. It highlights a continuous thread in communication—our persistent need to enrich written language and make it as expressive and nuanced as spoken language. Thus, the 1881 Puck magazine’s emoticons serve not just as a quirky historical footnote, but as a testament to the inventive spirit inherent in human communication.