Starting a fire with ice might sound like an oxymoron, but it is indeed a practical and fascinating survival skill, leveraging basic physics to generate heat from one of the coldest substances. The process revolves around carving a piece of clear ice into the shape of a lens. This ice lens functions just like a glass lens, focusing rays of sunlight into a single point. When sunlight passes through the ice, the concentrated light beam it forms can reach a high enough intensity to ignite combustible material.

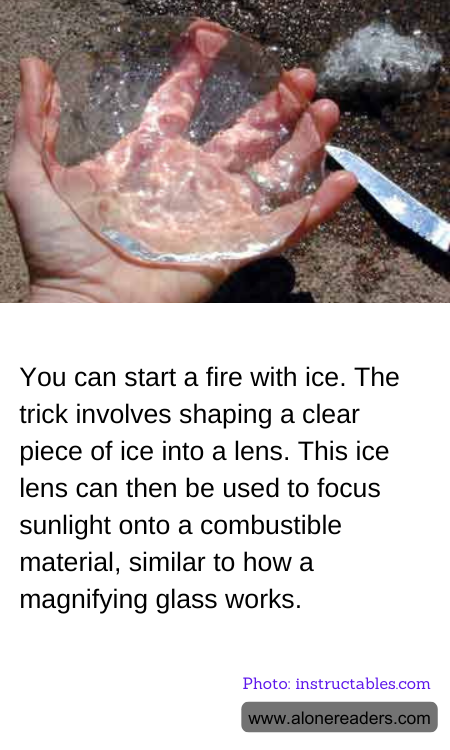

The key to this method is both the clarity and the shape of the ice. Ideally, the ice must be clear, as cloudy or opaque ice contains impurities and air bubbles that scatter sunlight, reducing the focus and intensity of the sun’s rays. Once a suitable piece of ice is found, it is shaped into a convex lens, typically with a smooth surface. To shape the ice, you can use the warmth of your hands, a knife, or even the smooth edge of a metal can. The thickest part of the ice lens should be at the center, tapering off towards the edges, much like a traditional magnifying glass.

Achieving the perfect curvature requires some patience and skill, as the lens needs to be smooth and uniformly thick to effectively concentrate sunlight. The process involves melting and smoothing the ice by hand to refine the lens shape. Once the ice is shaped appropriately, it’s critical to position the lens correctly in direct sunlight, aiming the focal point at a pile of dry, fine tinder, such as leaves, paper, or small twigs. Adjust the distance between the ice lens and the tinder until you find the smallest, most intense focal point; this is where the temperature will be highest.

Although this might seem like a less conventional method of starting a fire, especially in a survival situation, it's a viable technique in conditions where sunlight is strong and ice is available. This method not only demonstrates an important survival skill but also provides a clear, practical lesson in optics and the properties of light. As intriguing as it is, practice is necessary to master the technique, so experimenting beforehand rather than relying solely on this method in an emergency would be advisable. This unique use of natural resources could be a lifesaving skill, blending knowledge of natural science with practical ingenuity.