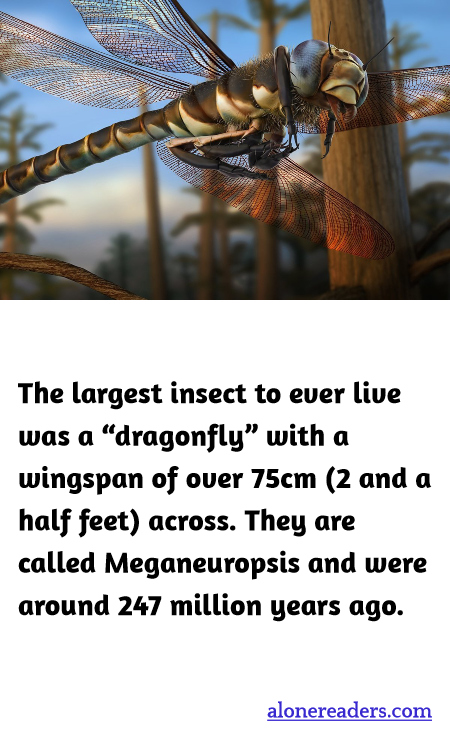

Walking through prehistoric landscapes, one could have encountered a truly spectacular sight: the Meganeuropsis, an extinct genus of griffenflies often hailed as the largest insects to have ever lived. Predominantly resembling modern-day dragonflies, these colossal creatures graced our planet approximately 247 million years ago, around the Permian period, although some lived during the late Carboniferous.

The most striking feature of the Meganeuropsis was its immense wingspan, which extended over 75 centimeters (about 2 and a half feet). This gigantic wingspan helped it to glide effectively through the dense, oxygen-rich prehistoric atmosphere, an environment that supported the growth of such large insect species. Their size not only made them formidable predators but also speaks to the unique conditions of the Earth at the time that supported such biodiversity.

Fossil records show that these giant insects had powerful mandibles which they likely used to prey on other insects and possibly small amphibians. Their reign as aerial predators came to a close with the Permian extinction event, which significantly altered the planet's climate and atmosphere. This event not only marked the end of the Meganeuropsis but also dramatically decreased the oxygen levels that supported such large arthropod sizes.

The existence of Meganeuropsis and similar large insects offers valuable insights into the planet's historical atmospheric conditions and the adaptational biology of prehistoric life. The study of such giant insects continues to provide valuable clues into the evolutionary processes that shape life on Earth, illustrating how creatures great and small adapt to their surroundings over the millennia.