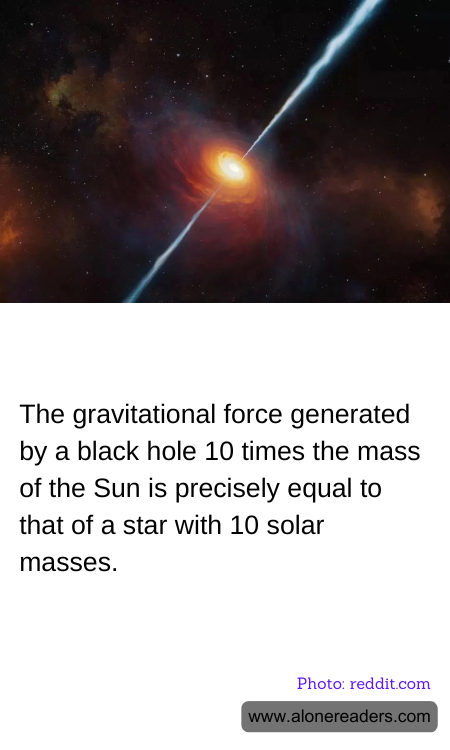

A black hole is a celestial object of immense gravitational power, from which nothing, not even light, can escape once it crosses the event horizon—the boundary around the black hole. The gravitational force it exerts can seem mysterious and exotic, but in many ways it functions similarly to any other mass in the universe.

A black hole with a mass 10 times that of the Sun would exert the same gravitational force as any other object of the same mass at the same distance. This is a consequence of Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation, which states that every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

This equivalence means that if a star with 10 solar masses were replaced by a black hole of the same mass, objects in orbit around the star would continue their path unaffected by the change. The gravitational force in both cases—emanating from the 10 solar mass star and from the black hole—is identical, preserving the dynamics of the stellar system or any objects interacting gravitationally with that mass.

It's important to address a common misconception: a black hole does not 'suck' objects like a vacuum cleaner. Instead, objects fall into it in the same way they might fall into a star or planet if they get too close. When an object approaches within a certain critical radius, known as the Schwarzschild radius, at which the escape velocity equals the speed of light, it will inevitably fall in and be unable to escape, essentially becoming part of the black hole.

Overall, despite their mysterious nature and extraordinary features, black holes interact gravitationally with their surroundings in predictable ways according to classical physics. Their influence on surrounding matter follows the same principles that govern the interactions of more familiar celestial bodies like stars and planets. This highlights an intriguing aspect of black holes: despite being extraordinary in terms of the conditions at their cores and their ability to warp spacetime profoundly, their interactions with distant objects are governed by the same laws that Isaac Newton first set down over three centuries ago.