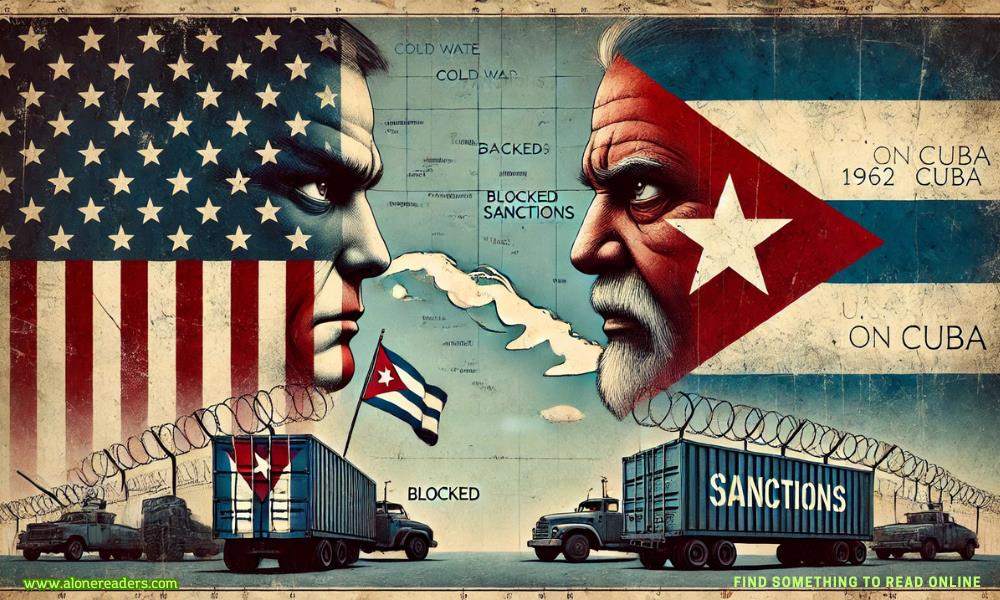

The U.S. embargo on Cuba, officially known as the Cuban Trade Embargo, stands as one of the longest-running trade and economic sanctions in modern history. Instituted in 1962 during the height of Cold War tensions, it was a direct response to the Cuban Revolution and the subsequent rise of Fidel Castro’s communist government, which aligned itself closely with the Soviet Union. Despite the dissolution of the USSR in the early 1990s and numerous geopolitical shifts since, the embargo remains largely intact, raising ongoing questions about its purpose, efficacy, and relevance in the modern era.

The roots of the embargo lie in the early 1960s when the United States, alarmed by the nationalization of American-owned businesses and properties in Cuba without compensation, began severing economic ties. Initially, in 1960, the U.S. restricted the export of all goods except food and medicine. By February 1962, President John F. Kennedy expanded the measures into a full trade embargo, prohibiting all imports from and exports to Cuba. The embargo was codified into law by the 1992 Cuban Democracy Act and further tightened by the Helms-Burton Act of 1996, which made the lifting of the embargo contingent upon democratic reforms in Cuba and compensation for confiscated properties.

For decades, the embargo served as both a symbol and a tool of U.S. opposition to communist regimes. During the Cold War, it was justified as part of a broader strategy to isolate and pressure Cuba economically, encouraging internal resistance and regime change. However, rather than weakening the Castro government, the embargo often became a rallying point for Cuban nationalism and anti-American sentiment. Fidel Castro skillfully used the embargo as a scapegoat for economic difficulties and as a justification for continued authoritarian rule.

Internationally, the embargo has drawn widespread criticism. The United Nations General Assembly has repeatedly passed resolutions condemning it, with the vast majority of member states voting in favor of ending the sanctions. Critics argue that the embargo has inflicted suffering on ordinary Cubans while failing to achieve its political objectives. Access to goods, medicine, and technology has been severely restricted, contributing to economic stagnation and hardship. Moreover, the extraterritorial provisions of the Helms-Burton Act have strained U.S. relations with allies and trading partners, who object to the U.S. imposing its policies on foreign companies doing business with Cuba.

Despite these criticisms, domestic politics in the United States have played a significant role in sustaining the embargo. Florida’s large Cuban-American population, particularly those who fled the island after the revolution, have traditionally supported hardline policies toward the Castro regime. Politicians from both parties, mindful of Florida’s electoral importance, have often hesitated to advocate for a full repeal. Even as public opinion has shifted—polls now indicate that a majority of Americans support normalizing relations—the embargo remains a politically sensitive issue.

There have been moments of thaw. Under President Barack Obama, significant steps were taken toward normalizing U.S.-Cuba relations. In 2014, the Obama administration announced a major policy shift, leading to the restoration of diplomatic ties, the reopening of embassies, and the easing of travel and commerce restrictions. Obama visited Cuba in 2016, becoming the first sitting U.S. president to do so in nearly 90 years. These developments were hailed as a historic break from the Cold War past and a move toward pragmatic engagement.

However, much of this progress was reversed under the Trump administration, which reinstated many restrictions and designated Cuba a state sponsor of terrorism shortly before leaving office. The Biden administration has maintained a cautious approach, easing some restrictions on travel and remittances but stopping short of a full return to Obama-era policies. Critics argue that this hesitance reflects the enduring influence of anti-Castro lobbying groups and the broader inertia of U.S. foreign policy.

The continued enforcement of the embargo raises critical questions about its purpose in the 21st century. The Cold War ended more than three decades ago, and the Soviet Union—the principal threat that justified the embargo’s inception—no longer exists. While Cuba remains a one-party state with a poor human rights record, it is no longer a major player on the global stage. The embargo now appears less as a strategic necessity and more as an outdated remnant of ideological conflict.

Economically, the embargo has hurt both sides. American businesses are barred from entering a potentially lucrative market just 90 miles off the coast of Florida. Agricultural producers, in particular, have lobbied for access to Cuban markets, arguing that U.S. exports could play a significant role in meeting the island’s needs while benefiting American farmers. Meanwhile, Cuba continues to face chronic shortages and an underperforming economy, problems that are exacerbated by, though not solely attributable to, U.S. sanctions.

Humanitarian concerns are also at the forefront of debates around the embargo. Although food and medicine are technically exempt, restrictions on financial transactions and shipping have made it difficult for humanitarian aid to reach the island efficiently. During times of crisis, such as natural disasters or the COVID-19 pandemic, these complications have had real consequences for the health and well-being of the Cuban population.

Supporters of the embargo argue that lifting it without major reforms would reward an authoritarian regime and reduce pressure for political change. They contend that economic engagement would strengthen the government rather than civil society, as the state controls most sectors of the economy. Nonetheless, decades of sanctions have not led to democratization. Instead, Cuba has developed alternative alliances and sources of support, particularly from countries like Venezuela, Russia, and China.

The embargo has also become a point of contention within Latin America, where many governments view it as an example of U.S. imperialism. The policy complicates regional diplomacy and undermines efforts at collaboration on shared challenges such as migration, public health, and environmental protection. As global attitudes evolve and the international consensus against the embargo grows, the United States increasingly finds itself isolated in its stance.

In the end, the U.S. embargo on Cuba stands as a relic of a bygone era—an enduring monument to Cold War fears and ideologies. Its persistence reflects the complexities of American politics, the power of symbolism in foreign policy, and the challenges of reconciling historical grievances with present-day realities. While its original justification may have faded, its impact continues to shape the lives of millions and the future of U.S.-Cuba relations. Whether it will be eventually lifted or reformed remains uncertain, but the debate over its relevance and morality is far from over.