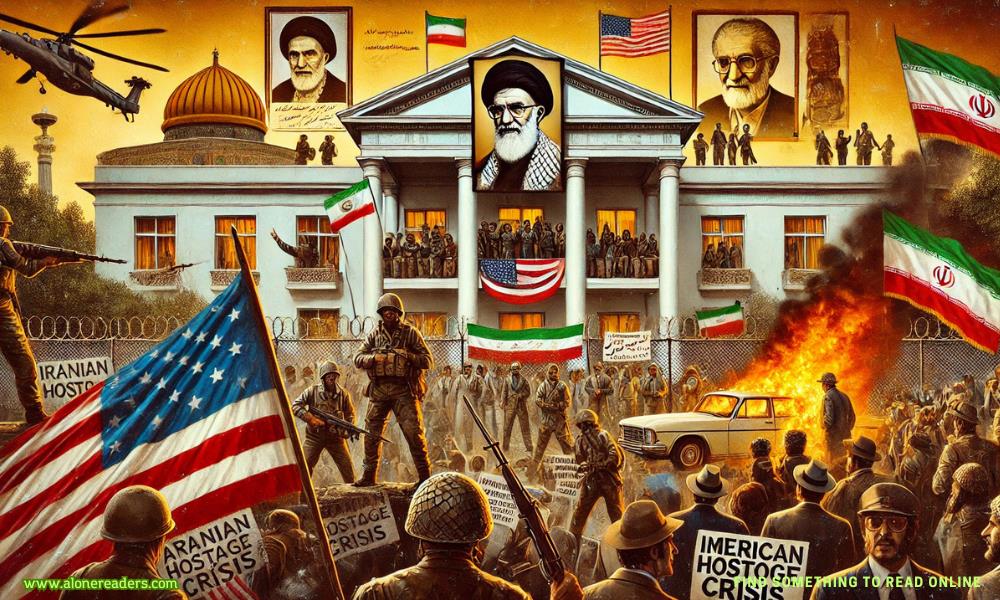

The Iranian Hostage Crisis, spanning from November 4, 1979, to January 20, 1981, remains one of the most defining episodes in the history of United States-Iran relations. This 444-day ordeal involved the seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and the captivity of 52 American diplomats and citizens by Iranian student revolutionaries. This event was not just a political conflict; it represented a seismic shift in Middle Eastern geopolitics, the rise of radical Islam in governance, and the onset of a decades-long animosity between Iran and the United States that persists in many forms today.

The roots of the crisis are entangled with decades of tension, beginning long before the embassy takeover. In 1953, the CIA helped orchestrate a coup in Iran that deposed the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, who had moved to nationalize Iran’s oil industry, threatening Western economic interests. The coup reinstated the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who ruled with increasing authoritarianism and strong support from the United States. His regime became synonymous with wealth, Westernization, and brutal suppression of dissent, particularly through his secret police force, SAVAK. Over time, this generated deep resentment among the Iranian population, who saw the Shah as a puppet of American imperialism and a betrayer of Islamic and nationalistic values.

By 1979, this resentment had reached a boiling point. A massive popular uprising, drawing support from a diverse coalition of Islamists, leftists, nationalists, and everyday citizens, forced the Shah into exile. In February 1979, the exiled religious leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned to Iran and established an Islamic Republic after overthrowing the monarchy. This transformation unsettled the West, especially the United States, which had long counted on Iran as a key ally in the Middle East.

Matters escalated dramatically when, in October 1979, President Jimmy Carter allowed the ailing Shah to enter the U.S. for medical treatment. This move, perceived in Iran as a sign that the U.S. might be plotting another coup to reinstate the Shah, sparked outrage. On November 4, 1979, a group of Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. They overpowered security personnel and took 66 American hostages, 52 of whom would remain in captivity for more than a year. The students claimed to act on behalf of the revolution, demanding the Shah’s return to Iran to stand trial and seeking to expose U.S. interference in Iranian affairs.

The Carter administration, caught off guard, immediately faced a complex diplomatic and political nightmare. Domestic outrage in the United States surged, while media coverage brought the hostage crisis into American living rooms night after night. Every moment of the standoff was broadcast and dissected, significantly influencing the public perception of President Carter's leadership. Diplomacy with the new Iranian regime proved extremely difficult, as Khomeini and his circle used the crisis to consolidate power internally, marginalize moderate factions, and rally the population around anti-American sentiment.

In an effort to resolve the situation, Carter attempted both diplomatic negotiations and economic sanctions. One of the most dramatic moves came in April 1980 with Operation Eagle Claw, a risky and ultimately disastrous rescue mission that ended in failure and the deaths of eight American servicemen in the Iranian desert. The operation’s failure further humiliated the United States and diminished Carter’s standing at home and abroad.

Iran, for its part, used the hostages as a bargaining tool and as propaganda to solidify its new ideological position. During the early stages of the crisis, students released women and African American hostages, framing their actions within a broader anti-imperialist and anti-racist ideology. But for the rest of the hostages, daily life was harsh. They were often kept in solitary confinement, blindfolded, subjected to mock executions, and denied basic liberties.

Throughout 1980, the crisis became increasingly entangled with American domestic politics. Carter’s inability to bring the hostages home became a focal point in his unsuccessful reelection campaign. The crisis helped fuel the rise of Ronald Reagan, who campaigned on a platform of restoring American strength and decisiveness in foreign affairs. Ironically, negotiations for the release of the hostages intensified just as Carter was leaving office. Through the mediation of Algeria, the U.S. and Iran reached an agreement known as the Algiers Accords.

On January 20, 1981, the very day Reagan was inaugurated, the hostages were released. The timing of the release was widely interpreted as a final insult to Carter and a calculated move by Iran to deny him a political victory. The terms of the release included a U.S. pledge not to intervene in Iranian affairs, the unfreezing of Iranian assets, and the establishment of a claims tribunal to address financial disputes between the two countries.

The aftermath of the Iranian Hostage Crisis left lasting scars. In the United States, the event became a symbol of perceived American weakness and vulnerability, leading to a more aggressive foreign policy posture under Reagan. For Iran, the crisis cemented the revolution’s success and marked a decisive break from Western influence. The diplomatic ties between the two nations were severed and have not been fully restored since. The crisis also triggered a redefinition of international law regarding diplomatic immunity and sparked discussions around counterterrorism and hostage negotiation protocols.

In cultural memory, the hostage crisis has lived on through documentaries, books, films like "Argo," and political discourse. It was one of the first major international events to play out in real time via 24-hour news coverage, laying the groundwork for the modern media’s role in shaping foreign policy narratives. It also highlighted the growing complexity of Middle Eastern politics, where domestic revolutions and foreign policy could no longer be cleanly separated.

More than four decades later, the Iranian Hostage Crisis remains a pivotal moment in global history. It redefined the rules of engagement between the West and revolutionary governments, demonstrated the power of symbolism and public spectacle in international relations, and ushered in a new era of confrontation between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran. It is a stark reminder that diplomatic standoffs are not just about state actors and their interests, but about ideologies, historical grievances, and the people caught in the middle. The legacy of the hostages, the revolutionaries, and the leaders involved still echoes through the halls of power in both Tehran and Washington.