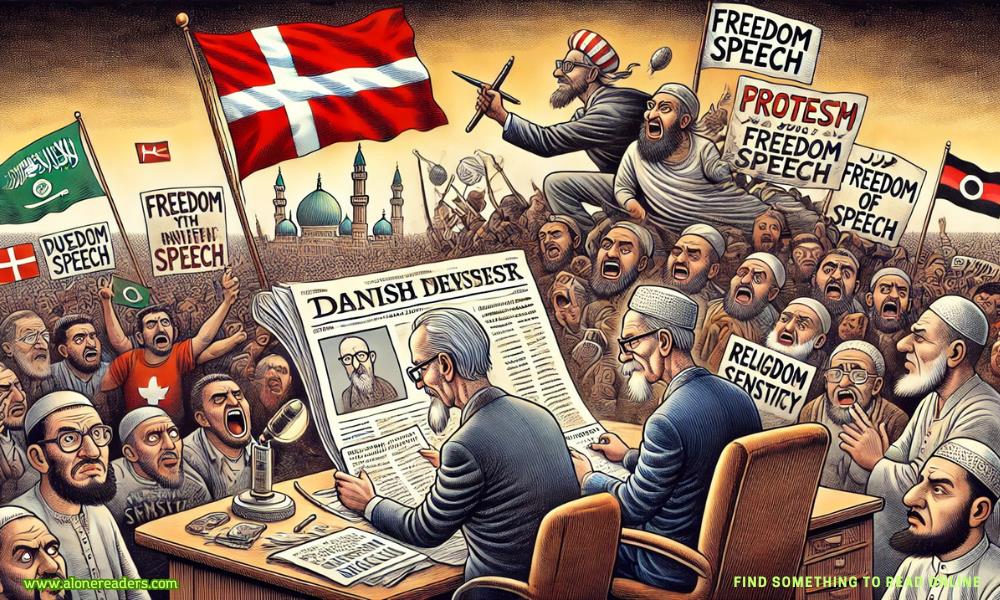

In 2005, Denmark became the epicenter of a profound and polarizing global controversy that highlighted the fragile intersection of free speech, religious reverence, and cultural misunderstanding. The Danish Cartoon Crisis, triggered by the publication of twelve editorial cartoons depicting the Islamic Prophet Muhammad in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, became more than just a national event. It quickly evolved into an international flashpoint, sparking violent protests, diplomatic crises, and an enduring debate about the limits of expression and the responsibilities that come with it.

The origin of the crisis lay in a cultural and political context already brimming with tension. In the early 2000s, Europe was grappling with questions surrounding immigration, integration, and the role of Islam in secular societies. In Denmark specifically, debates around multiculturalism were intensifying, with growing public discourse questioning whether Muslim communities were assimilating into Danish values, particularly regarding freedom of speech, gender equality, and secular governance. Against this backdrop, Jyllands-Posten, a right-leaning newspaper known for its critical stance on political correctness, commissioned and published cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad on September 30, 2005.

The newspaper claimed the publication was a response to perceived self-censorship among Danish artists, after reports that illustrators had refused to work on a children's book about Muhammad due to fear of reprisal. Asserting the importance of free expression, the editors said their intent was to challenge this fear and stimulate debate about the role of Islam in Danish public life. However, to many Muslims, the act was not an invitation to dialogue but an unforgivable provocation. In Islamic tradition, any visual depiction of the Prophet Muhammad is considered highly disrespectful, and several of the cartoons added insult by linking Islam to terrorism.

The reaction among Denmark’s Muslim community was swift and furious. Local imams and community leaders organized protests and appealed to Danish authorities, demanding apologies and legal action. However, the Danish government, led by Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen, refused to interfere, citing constitutional protections on press freedom and denying any government responsibility for the actions of an independent newspaper. This refusal to apologize was interpreted by many in the Muslim world as indifference—or even hostility—toward Islamic values.

As Danish Muslims took their grievances abroad, the issue escalated dramatically. Delegations of Muslim leaders traveled to the Middle East to rally support, distributing a dossier that included the twelve original cartoons along with three other inflammatory images, which were never published by Jyllands-Posten but were falsely attributed to the newspaper. By early 2006, outrage had spread across the Muslim world. Massive protests erupted in countries like Pakistan, Iran, Syria, and Indonesia. Some turned violent, with Danish embassies attacked and torched in Damascus and Beirut. At least 200 people were reported killed in various incidents linked to the unrest. Several European consulates were targeted, and calls to boycott Danish products swept through Muslim-majority countries, inflicting significant economic damage on Danish exporters.

The global response revealed deep fault lines in the relationship between the Islamic world and the West. In Western countries, the controversy was largely framed as a battle for free speech—a cornerstone of liberal democracies. Defenders of Jyllands-Posten insisted that while the cartoons might have been offensive, censoring them would set a dangerous precedent. Critics, on the other hand, argued that freedom of expression should be tempered by social responsibility and that knowingly publishing images offensive to a billion people worldwide amounted to cultural arrogance, not courage.

In Muslim-majority nations, the issue was viewed through a different lens. The cartoons were seen not as isolated pieces of satire, but as part of a broader pattern of Western disrespect and hostility toward Islam. The Danish government's refusal to condemn the cartoons confirmed for many what they already believed—that the West used free speech as a shield to demean Islam under the guise of liberalism. The protests, in their view, were not just about cartoons, but about centuries of colonialism, discrimination, and marginalization.

The Danish Cartoon Crisis also had profound consequences for global diplomacy, journalism, and security. Several newspapers in Europe and elsewhere republished the cartoons in solidarity with Jyllands-Posten, leading to fresh waves of protest. In 2008 and 2010, attacks were plotted or carried out against cartoonists and editors involved in the original publication. Most notably, in 2015, the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo—which had also republished the Danish cartoons—was attacked by Islamist gunmen, leaving 12 dead and reigniting the debate on whether satire should have limits when religion is involved.

Within Denmark, the crisis reshaped national identity and policy debates. It hardened public opinion against what many Danes saw as growing intolerance among immigrant communities, and it spurred legislative and political efforts aimed at better integration—but also led to rising anti-Muslim sentiment. For Danish Muslims, the events were deeply alienating. Many felt vilified, caught between defending their faith and being seen as threats to Danish values. The sense of exclusion lingered long after the embassies were rebuilt and the boycotts ended.

Looking back nearly two decades later, the Danish Cartoon Crisis is widely regarded as a defining moment in the 21st-century clash between liberal democratic values and religious sensitivities. It was one of the first truly global controversies to be shaped and amplified by the internet and modern media, demonstrating how quickly local disputes can escalate into international crises in an interconnected world. The crisis also posed critical questions that remain unresolved: Where should the line be drawn between free expression and incitement? Can societies maintain both cultural pluralism and absolute freedom of speech? And is mutual respect between fundamentally different worldviews truly possible in a globalized age?

Perhaps the most sobering legacy of the Danish Cartoon Crisis is the growing realization that rights and values we often assume to be universal—such as free speech—are not interpreted the same way across cultures. While freedom of expression is enshrined in many democratic constitutions, its application in multicultural societies requires nuance, empathy, and restraint. This does not mean yielding to threats or abandoning core principles, but it does suggest that in an era of rapid communication and cultural convergence, the responsibility of expression is just as vital as the right.

In the end, the Danish Cartoon Crisis remains a case study in what happens when principle collides with perception, and when the power of the press meets the power of belief. It is a reminder that freedom of speech is a double-edged sword—capable of illuminating injustice, but also of deepening divides if wielded without understanding. As societies continue to navigate the delicate balance between openness and offense, the lessons of 2005 linger, unresolved and urgently relevant.