When Bashar al-Assad assumed the presidency of Syria in 2000, there was widespread speculation that the young, Western-educated leader might steer the country toward political and economic modernization. His succession, following the death of his father Hafez al-Assad, marked the beginning of what was initially dubbed the "Damascus Spring"—a brief period of cautious optimism among reformists. Bashar promised economic reforms, development, and a degree of openness that stood in stark contrast to his father’s rigid Ba'athist rule. However, by the end of the decade, the economic liberalization policies introduced under his leadership had produced a dual reality: rapid enrichment for a narrow circle of elites and growing hardship for the majority of Syrians. This imbalance laid much of the groundwork for the unrest that would erupt in the 2011 uprising.

Bashar's approach to economic reform was heavily influenced by a desire to modernize Syria's stagnant state-run economy without undermining the regime’s authoritarian control. Central planning and subsidies had long defined Syria’s socialist-leaning economy. But under Bashar, these policies began to shift in favor of market-oriented reforms: the lifting of trade barriers, partial privatization of state enterprises, relaxation of foreign exchange restrictions, and the encouragement of foreign direct investment. These moves were presented as essential for growth and development, yet the actual implementation revealed deep structural contradictions.

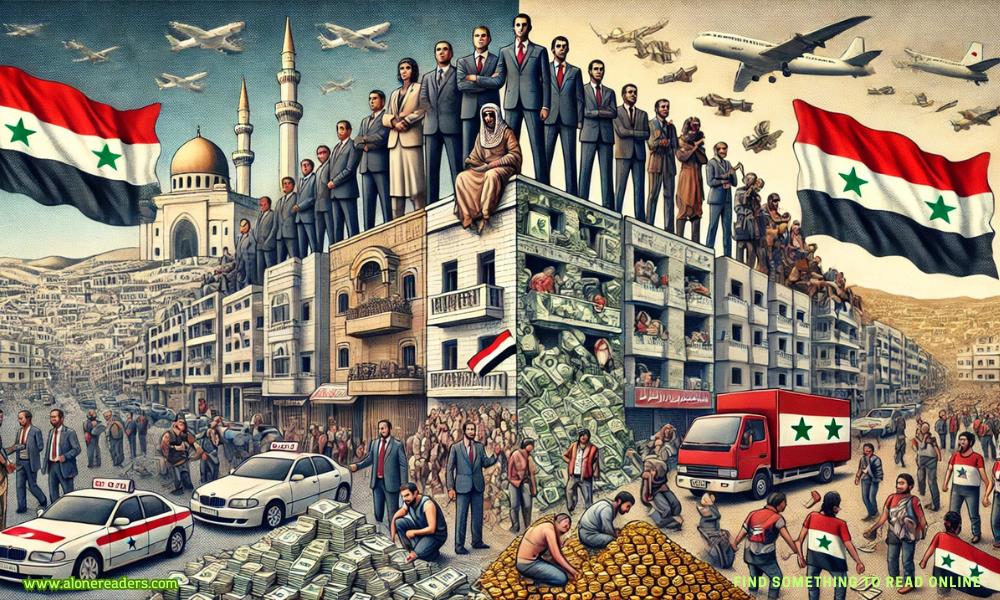

The liberalization process was neither transparent nor inclusive. Instead of fostering a competitive private sector or broad-based prosperity, it opened new avenues for regime-connected individuals—particularly members of the Assad family, loyal businessmen, and Ba'athist insiders—to consolidate their economic power. The commanding heights of the emerging private economy, from banking and telecommunications to construction and import monopolies, were captured by a handful of oligarchic families. Chief among them was Rami Makhlouf, Bashar’s cousin, who emerged as one of Syria’s wealthiest and most influential businessmen. Through preferential access to licenses, government contracts, and regulatory protections, Makhlouf came to dominate key sectors, including Syriatel, Syria's largest telecommunications firm.

This crony-capitalist model served two key functions for the regime. First, it created a dependent economic elite whose wealth and power were tied directly to regime survival, making them less likely to defect or support reforms that could democratize power. Second, it helped generate the illusion of economic dynamism and modernity, attracting Gulf investment and fostering limited urban development in Damascus and Aleppo. The sight of luxury hotels, new shopping centers, and private banks emerging in Syrian cities created the appearance of progress. Yet this growth was not inclusive; it failed to improve the conditions of rural populations, informal workers, and the shrinking middle class.

The social consequences of these policies were profound. Public sector employment, once a reliable pathway to stability for many Syrians, stagnated, even as inflation and the cost of living rose. The regime began to roll back subsidies on essentials such as fuel and food, a decision that disproportionately affected the poor and rural communities. While the elite enjoyed access to Western goods and private healthcare, most Syrians experienced declining access to quality education, job opportunities, and affordable housing. Income inequality worsened. Urban-rural disparities deepened. A sense of disenfranchisement spread among the country’s youth, particularly those who were educated but unable to secure meaningful employment.

Perhaps most crucially, the regime’s economic liberalization policies eroded the unwritten social contract that had existed under Hafez al-Assad. For decades, Syrians had accepted limited political freedoms in exchange for economic stability, subsidized services, and state employment. Bashar’s reforms upended that balance without offering a viable new one. The state no longer functioned as a guarantor of basic welfare for all, but rather as a facilitator of wealth accumulation for a select few. In doing so, it lost the trust of many Syrians who had previously been passive supporters or neutral observers of the regime.

Discontent simmered beneath the surface. While the regime continued to tightly control political dissent, small protests erupted sporadically over issues like corruption, land rights, and subsidy cuts. Civil society spaces were increasingly stifled, especially after the early optimism of the Damascus Spring was crushed by a wave of arrests and crackdowns. In rural areas, especially in the drought-affected northeast, whole communities faced economic ruin without adequate state support. The urban poor, many of whom lived in informal settlements, found themselves further marginalized. Meanwhile, the regime’s propaganda machine continued to tout the success of its economic reforms, presenting selective data and flashy development projects as signs of nationwide progress.

By the end of the 2000s, the contradictions in Syria’s economic liberalization were becoming too large to ignore. On one hand, GDP growth was averaging around 5 percent annually, a figure that Western financial institutions cited as evidence of reform success. On the other hand, unemployment—especially among the youth—remained dangerously high. Corruption was rampant. Land prices skyrocketed in major cities, pricing out even the middle class. The public’s perception was not of a government helping the nation modernize, but rather of a regime enriching itself and its allies at the public’s expense.

These dynamics would explode into full view during the Arab Spring in 2011, when widespread protests swept across the Middle East. In Syria, the uprising initially focused on demands for political freedom and dignity, but quickly evolved into an indictment of the entire system—including the economic injustices of the preceding decade. Protesters decried corruption, inequality, and elite privilege. The once-untouchable businessmen like Rami Makhlouf became symbols of a failed, rigged system. The regime responded not with reform, but with repression—plunging the country into a brutal civil war that continues to shape the region.

In retrospect, Bashar al-Assad's economic liberalization in the 2000s was a paradox. It was marketed as a step toward modernity, but it entrenched backward systems of patronage and inequality. It introduced market mechanisms, but without transparency or accountability. It promised prosperity, but delivered alienation and unrest. Rather than modernizing Syria, it accelerated the decay of the state-society relationship and helped sow the seeds of revolution. For Syrians, it was not just the absence of democracy that fueled rebellion—it was also the betrayal of economic justice.